Dr. Heston

Senior Thesis

December 9, 2014

Rethinking the Allegorical Portraits of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir

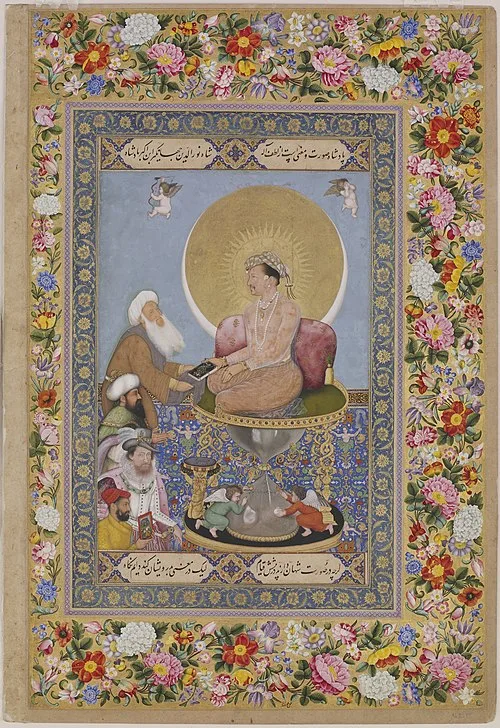

A prolific body of work created in the atelier, (kitabkhana), of the Mughal emperor, Jahangir (1605–1627), illustrates his vast and intimate knowledge of painting. Jahangir’s father, Akbar the Great (1556–1605), was devoted to the illustration of historical epics, Persian and Islamic as well as Indian. Although the paintings or miniatures were created before and after Jahangir’s ascension to the Mughal Throne, Jahangir’s main manuscript productions were executed at the court he established in Allahabad during his rebellion from his father (1600–1604). Later works reflect an increased interest in individual portraiture, and naturalistic plant and animal themes. By moving away from textually driven painting to the use of the album, (muraqqa), Jahangir’s artists became invested in the completion of individual works of art. An album, (muraqqa), contained a collection of works bound together. These works could include anything from animal studies, to allegorical works and portraits. They also contained works from a wide variety of cultures and time periods. This paper will focus on a select group of portraits often referenced as the allegorical portraits of Jahangir. Included in these are Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shayk, Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas, Jahangir Shooting his Enemy Malik Ambar, and Jahangir Triumphing Over Poverty (fig. 1, 2, 3 & 4). I have chosen to focus on the last three works all done by the same artist Abu’l Hasan. These works depart from the main body of Jahangir’s paintings by their individual representation of the Emperor, the wide range of allegorical sources upon which the imagery draws and, what I will call here, visionary representation of Jahangir’s desired depiction of his rule. This was not necessarily a reflection of the historical reality presented in the writings of his time. The common description of these works as allegorical portraits, I will argue, is an oversimplification of a complex syncretic image of imperial rule which is unique in its visionary elements.

Jahangir saw himself as a connoisseur of painting. There was not an artist from Jahangir or his father’s atelier that he did not claim to recognize by the artist’s brush stroke.

I derive such enjoyment from painting and have such expertise in judging it that, even without the artist’s name being mentioned, no work of past or present masters can be shown to me that I do not instantly recognize who did it. Even if it is a scene of several figures and each face is by a different master. I can tell who did which face. If in a single painting different persons have done the eyes and eyebrows, I can determine who drew the face and who made the eyes and eyebrows[^4].

Before his ascension to the Mughal Throne, Prince Salim (Jahangir) rebelled against his father and established a court with a separate atelier, (kitabkhana), at Allahabad. Stronge noted there was not a significant difference between the works produced by Akbar and Jahangir at this time[^1]. However, his creation of a separate court did allow for the establishment of artists who would later become prolific painters for Jahangir. One of these artists, Abu’l Hasan, the son of Aqa Riza, would take a special place in the eyes of Jahangir.

Abu’l Hasan the artist, who had been awarded the title of Nadiruzzaman [rarity of the time] presented a painting he had made for the opening page of the Jahangirnama since it was worthy of praise, he was shown limitless favor. Without exaggeration, his work is perfect, and his depiction is a masterpiece of the age. In this era he has no equal or peer. Only if Master Abul-Hayy and Master Bihzad were alive today would they be able to do him justice[^6].

Abu’l Hasan came to the court in Allahabad with his father at the age of twelve[^7]. Earlier works show his interest in copying European works that were brought to both Akbar and Jahangir’s courts by Jesuit missionaries[^8]. Additionally, in 1616, the introduction of English miniature portraits by James I’s ambassador, Sir Thomas Roe, the nephew of the famous miniaturist, Isaac Oliver, demonstrated a movement toward psychological and realist portraiture that was embraced by Abu’l Hasan in his visionary works of Jahangir[^9].

Jahangir’s albums included a wide variety of themes from Persian, to European Christian and secular works. He also had an interest in Christian-themed paintings of the Virgin Mary and of Jesus. A Jesuit missionary noted his fascination for these works even before he became the Emperor. A letter written by Xavier, a Jesuit missionary, and sent to Akbar’s court mentions that Prince Salim “was very angry with those who had conducted the Father, because they had not brought him any picture of Our Lady from Goa; and speaking to another, who was about to set out to those parts, he charged him to buy certain pieces which he desired to have, biding him above all things not to forget to bring a beautiful picture of Our Lady”[^10]. Writings by various authors note this fascination with European imagery and the competition between Akbar and Jahangir for power. They often include descriptions of the procurement of a painting intended for Akbar[^11]. It is unclear as to why Jahangir was so enamored by European works. It has been suggested that in an attempt to establish a divinely appointed lineage, Akbar and his historian, Abu’l Fazl, viewed the images of the Virgin Mary and Christ as a symbol of dynastic legitimacy. They did not view them as a messianic image in the way the Jesuit priests hoped, but as a representation of Queen Alanqua. The legend states that Queen Alanqua was visited by a divine light, resulting in the birth of triplet sons. One of these sons, who also contained the divine light, was the ancestor of Akbar. This established Akbar’s lineage as divinely sanctioned[^12].

Jahangir’s desire for European imagery then is not related to conversion to Christianity but as a source of imagery that described his own lineage through the Timurids. Furthermore, these images had familiar allegorical and symbolic meaning to Jahangir’s Persian and Indian artists.

Jahangir continued the portraiture ideals established by Akbar in the narrative portraits entitled Abu’l Hasan’s Celebration of Jahangir’s Ascension, ca 1605, and The Weighing of Prince Khurram, ca 1625, artist unknown (fig. 5 & 6). However, these miniatures began to show a subtle change in the representation of the Emperor as a more thoughtful ruler instead of the dynamic, and vigorous image contained in the representations of Akbar. Jahangir refined the imperial image. Jahangir’s images focused on courtly life instead of the dynamic action-oriented portraits of Akbar. The warm tones and busy nature of Abu’l Hasan’s Celebration of Jahangir’s Ascension contrast sharply with the surrealistic scenes of Jahangir. Jahangir is depicted as a single figure triumphing over his enemies. In the Ascension, Jahangir rides atop a large elephant. The two figures fill the arched palace gateway. Jahangir dressed in mustard yellow raises his arms in greeting to his people as trumpeters announce his entrance. The dramatic shifts in scale of the painting draw us to the individuals attending the celebration. This work reflects the works done in Akbar’s court in the late 16th Century. In addition, it shows the beginning of intense emotional representation that can be seen in three paintings of Jahangir: Embracing Shah Abbas, Jahangir Shooting his Enemy Malik Ambar, and Jahangir Triumphing over Poverty. These paintings provide glimpses into the ceremonial life of Jahangir and his court. They are valuable in understanding the imperial rule of Jahangir during the Mughal Period. They also exemplify the departure of Jahangir from courtly narrative in creating his allegorical or visionary works.

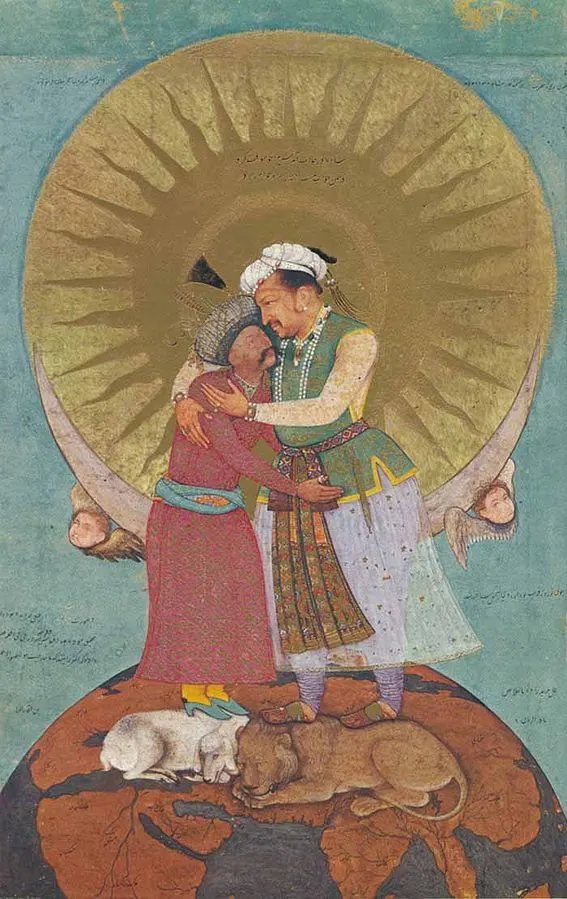

Jahangir was the first of the Mughal line to rule over “a fully functioning system of sacred kingship”[^14]. Akbar sought to establish harmony among the many religious and ethnic constituents in his empire. Jahangir furthered the concepts of imperial conquest with the help of his son, Prince Khurram (Shah Jahan). Prince Khurram won most of his victories during Jahangir’s reign. Lefèvre contends that Jahangir was the first emperor to, “claim religious leadership over both Shi’is and Sunnis. Jahangir was also the first to witness the effective transformation of the Safavids from saint-kings into staunch upholders of Imami Shi’ism”[^15]. The Safavid ruler, Shah Abbas, is part of a striking image of Jahangir, Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas. During this time period Shah Abbas embraced Imami Shi’ism and left the Sunni concepts of the caliphate. In Jahangir’s painting, the Shah is seen as a small, fragile ruler standing on top of a sleeping lamb. He appears as though he can barely stand on his own two feet. He looks up into the eyes of the robust and virile Jahangir. Jahangir embraces him as though he is holding him up while standing nobly on the sleeping lion. The European globe centers our view on India, but the lion covers most of the Shah’s empire as well as Jahangir’s empire. The relationship between the Mughal and Safavid empires starts with Babur, the first Mughal Emperor. Up until this point, Safavid Persia was the parent empire who offered protection to its son, the Mughal Empire. Humayun, Jahangir’s grandfather, spent a great deal of time in exile at the court of Shah Tahmasp. In creating this portrait, Jahangir expressed his desire to show that the Mughal Empire no longer needed the Safavid Empire for protection, just as the parent grows old and the son matures to take care of the aging parent. At the time of the painting, neither Shah Abbas, nor his kingdom were frail, or aging, but were currently taking the strategically located fort at Qandahar, in present-day Afghanistan, from Jahangir[^16]. This seems to be the relationship of these visionary paintings. They represent Jahangir’s expressed desires for his empire, but do not necessarily reflect historical reality.

Other authors theorize that Jahangir’s paintings were merely a reflection of his inner self. Moin puts forward an interesting interpretation of Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas. His interpretation is based on Jahangir’s displeasure with the Shah’s decision to nullify his saintly-king status in favor of Imami Shi’ism. He proposes we should, “read the painting as a reversal of the balance of spiritual power between the two dynasties; a century after Babur’s submission to Shah Ismail, the saint-king Jahangir had performed the ‘oneiric miracle’ of turning the Safavid [Shah Abbas] into his disciple”[^18]. Welch, in his discussion on Mughal Albums, puts forward the idea that, “several of Abu’l Hasan’s pictures served to blunt—even exorcize—Jahangir’s deeper anxieties by turning them into allegorical paintings… Fearful of losing the strategic fortress of Qandahar to the Safavids, Jahangir deemed that his Iranian rival Shah Abbas appeared in a well of light and made him happy”[^19].

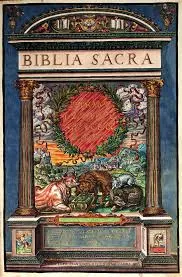

Koch believes that the imagery used by Abu’l Hasan could have been based on the Flemish engravings contained in the Antwerp Polyglot Bible[^20]. The Bible was presented to Emperor Akbar in 1580 by Jesuit Missionaries. Stronge adds that the fathers also presented Akbar with Abraham Ortelius’ atlas entitled Theatrum Orbis Terrarum[^9]. Koch also proposes, in a later article, an alternate allegory based on the Persian story of Majnun and Layla written by Nizami of Ghanja, as well as the image of King Solomon as the ideal ruler (fig. 7)[^21]. The link between the European engravings and the concept of King Solomon is demonstrated in the use of the predatory animals lying down with the prey. These allegorical representations would have established Jahangir as the ideal king who brought peace and prosperity to his kingdom. The key to understanding these allegories lies in the consistency of the visual reference in the three visionary paintings of the animals. It could also be where the reference to allegory ends, and symbolic representation replaces allegory as a tool to reference Jahangir’s own private visions that accompany each of Abu’l Hasan’s representations of the Emperor.

In the engraving of Pietatis Concordiae drawn by Pieter van der Borcht and engraved by Pieter van der Weyden, it symbolically references the ability of Messianic rule to bring peace among animals prophesied in Isaiah (fig. 8)[^22].

The wolf lies with the lamb,The panther lies down with the kid,Calf and lion cub feed togetherWith a little boy to lead them,The cow and the bear make friends,Their young lie together.The lion eats straw like the ox.The infant plays over the cobra’s holeInto the viper’s lairThe young child puts his hand.They do no hurt, no harm,On all my holy mountain,For the country is filled with the knowledge of YahwehAs the waters swell the sea. (Isaiah 11: 6–9)

The use of animals to enact events from stories would not have been a difficult concept for the Mughals to understand. For the Mughals, the assembly of peaceful animals would have connected with similar representations in the Persian and Mughal paintings of King Solomon as well as King Guyumar from the Shahnama (fig. 9)[^23]. Jahangir would have seen this as advantageous to his imperial image. King Solomon was considered to be the epitome of kingly graces. In the three allegorical paintings by Abu’l Hasan, the Emperor Jahangir is seen standing atop a globe on the back of a lion who lays down in harmony with the lamb.

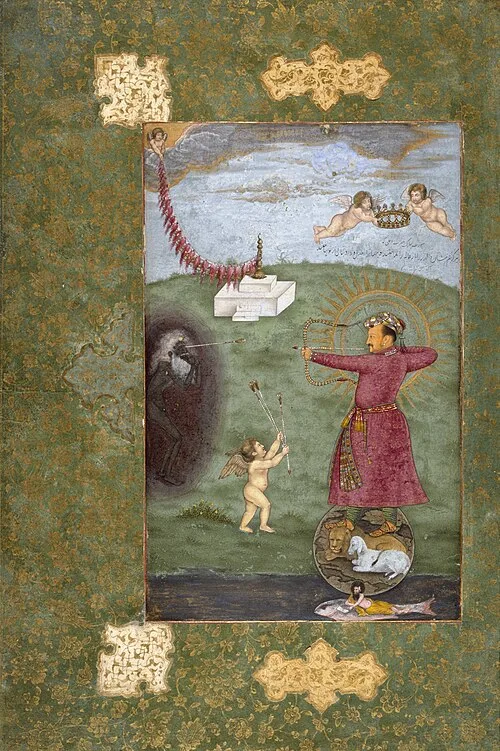

On the second title page of the Bible, an engraving by Van der Borcht of the Pietas Regia can be seen in reference to Jahangir Shooting the Head of Malik Ambar (fig. 10)[^24]. This would not seem so on first appearance. The Pietas Regia contains a compositional allegory that could have easily been interpreted by its intended European audience. However, this same allegorical meaning would not necessarily have been recognized in the Islamic world. In spite of these dissimilarities, Koch maintains that “the place of the female personification of regal virtue in the central Asia of the composition is taken by Jahangir, thus himself personifying ideal rulership”[^25]. The sword and arrow represent the difficult decisions that a leader is required to make. This is similar in representation to the stash of weaponry along the left-hand side of the Pietas Regia. The same compositional layout of the two vertical elements centered by a central figure and topped by a putto, are represented in both the painting and the engraving. As in Christian symbolism, with the right hand representing good and the left hand representing bad, Islamic symbolism also used the right-hand-side of the figure to represent good. In this image, the right-hand-side of Jahangir represented his familial lineage through the Timurid line. Jahangir is removing not just his personal enemy, but the enemy of the people.

In addition to the elements seen in the Pietas Regia, the artist added symbolism that would have been part of the Mughal Court. The gold chain placed at the foot of the Emperor is one such example. The gold chain installed by Jahangir in the royal court allowed anyone who felt that justice was not being fairly met to pull the chain and speak directly with Jahangir[^26]. Here we see the carefully balanced scales of justice hanging from the chain. This could possibly have symbolized that “no one finds this act to be unjust.” Furthermore, Robert Skelton interprets other symbols from the painting. He suggests that the large grey fish with a bull on its back is from an old Islamic cosmological concept presented in the poetry of the mystic, Farid al-din Attar, found in the Mantiq al-Tayr (1187)[^27].

At the beginning of the centuries God used the mountains as nails to fix the earth; and washed earth’s face with the waters of ocean. Then he placed the earth on the back of a bull, the bull on a fish, and the fish on the air[^28].

By incorporating both European and Islamic cosmology, Jahangir synthesizes a dynastic image that is purely Mughal in style. Koch interprets the likeness to the Pietas Regia, (a complex sixteenth-century European allegory), to mean, “…the Mughal artist did not simply copy but rather adapted the whole concept. The European model became, in fact, subject to an interpretatio Mongolica”[^29].

Although this image contained noble ideals, it did not necessarily represent the actual historical reality of the time period. Jahangir was in fact losing to Ambar. Jahangir’s son, Prince Khurram (Shah Jahan), was fighting this war for his father. Shortly after the war with Ambar, Prince Khurram rebelled. Some scholars believe that Jahangir chose to use European religious symbolism to create his dynastic image because it was neutral. Using neutral symbols encouraged harmony between Islam and Hindu because it allowed both to be respected. It created a common ground that was neither one nor the other. Skelton, in his analysis of the work, relates the image of Ambar and the owl to Mughal superstitions. In addition, he points out that the owl represents a play on words that referenced Ambar’s dark skin coloring[^32]. By removing the threat of Ambar, Jahangir could view himself as the protector of his family. In truth, Ambar was not removed, he died of old age. Ambar also helps Shah Jahan in his struggle to claim the Mughal Throne from his siblings and Jahangir’s wife, Nur Jahan[^33].

In the circa 1620 portrait of Jahangir Shooting Poverty, the underlying threats perceived by Jahangir no longer came from outside the empire but from within. Welch, in his analysis, comments that the threats were “from embittered courtiers, from members of the imperial family, and from the emperor’s introspective mind…”[^34]. Abu’l Hasan’s image of the warrior king absolving his people from the threat of poverty has a similar composition to that of Jahangir Shooting his Enemy Ambar Malik. Jahangir is portrayed as a warrior and not as a spiritual leader. He wears a richly brocaded robe of costly silk while standing firmly on the head and back of the lion. His head and upper torso are surrounded by a radiating, double-ringed halo. Putti hover over his head on the right-hand-side of the image. The putti hold aloft the crown of the Timurid kings. Under the crown is the phrase, “Blessed portrait of His supreme Majesty who dispatches his eager shafts into poverty and who, through his rectitude and firmness is laying new foundations for the world”[^35]. In the left upper corner of the painting, a putti holds fast to the chain of justice. This chain of justice was also depicted in Jahangir Shooting his Enemy Ambar Malik. The symbolism of the putti, eagerly helping Jahangir to avenge the effects of poverty, could be a reference to the newly established East India Company. These images, located in various albums, and possibly compiled by either Jahangir or Shah Jahan, represent a king that seeks to be the hero of his people.

As a Sunni ruler, Jahangir is considered the caliph of the Prophet Mohammad by the orthodox Muslim courtiers. Therefore he was deemed the protector of the Islamic faith. In the training received from his father, Akbar, Jahangir understood the need to balance the ulema (people of the book), with his Hindustani nobles. His choice of subject matter for Abul Hasan’s allegorical or visionary paintings describes the choices made by patron and the artist in establishing an allegorical persona. “In most cases, the allegorical disguise serves to highlight some specific feature—recognized, wished for, even regretted—of the person portrayed”[^36]. Jahangir sought to establish a deeply probing look at the world around him and to record this visually. However, this goal is inconsistent with the focus of his allegorical painting. Generally, these works endeavored to record the inner psychological pictures created by the Emperor. Beech, in The Grand Mogul, explains, “The differences between works by different Jahangir painters are often very subtle, for the painters worked in response to their patron, and became virtual extensions of his personality…”[^37]. They recorded dreams, and visions maintaining a spiritual connection with the bestowers of royal power—the Chisti Sufi and the visionary embodiment of Jahangir as a “universal ruler”. In spite of their power, Jahangir constantly balanced them politically. Jahangir embraced the Hindu concept of rulership as a protector, or father figure, to his people. Jahangir’s determination to create a universal dynastic image, and his obsession with the working of the world, visually distinguishes him in his allegorical or visionary representations.

The design of an allegory was used in literary, as well as visual, context. It was the extending of a metaphor. Merriam-Webster defined this as “A story in which the characters and events are symbols that stand for ideas about human life or for political or historical situations”[^39]. During the High Renaissance allegories became popular in painting. Works such as Filippino Lippi’s The Allegory of Music was a genre that was seen by the Mughal Emperors through Jesuit Missionaries (fig. 11)[^38]. Themes such as Orpheus and the representation of virtues and vices through classical Greek and Roman imagery were associated with the popularity of the allegory in the Sixteenth Century. In addition to these allegories, Jahangir was familiar with traditional Persian stories such as Majnun and Layla, and the concept of King Solomon as the ideal ruler allegorical. These represent the moral lessons of the age. Jahangir’s allegorical works used the imagery from these stories. However, they do not represent a conceptualized visual allegory in the same respect as other allegories. One example of this is Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas which is a visual interpretation by Abu’l Hasan of a dream Jahangir had. Welch refers to Jahangir’s works as “wish fulfilling fantasies”[^34]. Ettinghausen describes them as a “dream picture”[^42]. In light of the diversity of their religious and cultural symbolism, they remain “at best an innovative iconography”[^42]. Although iconography and allegories both substitute well-known images for ideas, they do so differently. Icons behave as signs to represent ideas or people through systematic imagery. Allegories, on the other hand, rely not only on the identification of symbols, but also literary references. Allegories “depend on a kind of transparency of means in the simple sense that, as the metaphorical language of usual interpretation implies, it is possible to ‘see through’ the surfaces of the work to its meaning”[^43]. We do not have the ability to fully understand the allegorical theme of these works, or even if they were intended as an allegorical representation of Jahangir’s ideals because the albums containing the works have been disbanded. We do not know what was originally bound with them. This leaves us with an image that has many possible layers of interpretation.

It is clear that Jahangir developed an imperial image protocol that used European, Persian, Islamic, and Indian Symbolism. He also created a unique representation of himself and his boundaries within a world of constantly changing boundaries. He sought to establish himself as the divine ruler over his empire—an empire he saw as universal. His dynastic image was linked to a past through his father’s divinity, and his Timurid lineage. Its purpose was to maintain Jahangir as “Shah of Shahs.” It was also to reinforce his “divinely ordained role from birth” sanctioned by the Chisti Sufi Order. However, simply assigning these images to the category of “allegory,” in a European-centric context, reduces the complex and nuanced importance of these images to Jahangir’s leadership. Their dream-like or visionary representations set them apart both from the main body of Jahangir’s works as well as from the normally accepted concept of allegory.

Footnotes

[^1]: Susan Stronge, Painting for the Mughal Emperor: The Art of the Book, 1560–1660 (London: V&A Publications, 2002), 112.

[^2]: Terence McInerney, “Three Paintings by Abu’l Hasan in a Manuscript of the Bustan of Sa’di,” in Arts of Mughal India: Studies in Honor of Robert Skelton (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2004), 81–82.

[^3]: Milo Cleveland Beach, Mughal and Rajput Painting (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 82.

[^4]: Jahangir and W. M. Thackston, The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India (New York: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Association with Oxford University Press, 1999), 268.

[^5]: Stronge, Painting for the Mughal Emperor, 112.

[^6]: Jahangir and W. M. Thackston, The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India (New York: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Association with Oxford University Press, 1999), 268.

[^7]: Milo Cleveland Beach, “The Mughal Painter Abu’l Hasan and Some English Sources for His Style,” The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 38 (January 01, 1980): 18.

[^8]: Beach, “The Mughal Painter Abu’l Hasan and Some English Sources for His Style,” 17.

[^9]: Stronge, Painting for a Mughal Emperor, 138.

[^10]: Beach, Mughal and Rajput Painting, 70. Also quoted in Som Prakash Verma, Interpreting Mughal Painting: Essays on Art, Society, and Culture (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009), 99.

[^11]: Ibid., 99.

[^12]: Gauvin Alexander Bailey, “The Indian Conquest of Catholic Art: The Mughals, the Jesuits, and Imperial Mural Painting,” Art Journal 57, no. 1, The Reception of Christian Devotional Art (April 01, 1998): 28.

[^13]: Beach, “The Mughal Painter Abu’l Hasan and Some English Sources for His Style,” 24.

[^14]: Corinne Lefèvre, “The Majālis-i Jahāngīrī (1608–11): Dialogue and Asiatic Otherness at the Mughal Court,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55, no. 2/3, Cultural Dialogue in South Asia and Beyond: Narratives, Images and Community (sixteenth–nineteenth Centuries) (January 01, 2012): 265.

[^15]: Lefèvre, “The Majālis-i Jahāngīrī,” 265.

[^16]: Ebba Koch, “The Symbolic Possession of the World: European Cartography in Mughal Allegory and History Painting,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55, no. 2–3 (2012): 557.

[^17]: Lefèvre, “The Majālis-i Jahāngīrī,” 269.

[^18]: Located in Moin, Islam and the Millenium. Quoted in Lefèvre, “The Majālis-i Jahāngīrī,” 269.

[^19]: Stuart Cary Welch et al., The Emperors’ Album: Images of Mughal India (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), 107.

[^20]: Ebba Koch, “The Mughal Emperor as Solomon, Majnun, and Orpheus, or the Album as a Think Tank for Allegory,” Muqarnas 27 (January 01, 2010), 286.

[^21]: Koch, “The Mughal Emperor as Solomon, Majnun, and Orpheus,” 278.

[^22]: Ebba Koch, Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology: Collected Essays (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001), 2.

[^23]: These sources would have been familiar to Jahangir and his court artist: “Anwar-I Suhayli, and Iyar-I Danish, Abul Fazl’s version of the famous Kalilah wa Dimnah (completed in 1588)… peace among the animals brought about by the justice of the ruler in the earliest Mughal writing: Khwandamir in His Qanunpi Humayuni written in 1533–34, Uses metaphors similar to the Biblical ones” Koch, Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology, 2.

[^24]: Koch, “The Mughal Emperor as Solomon, Majnun, and Orpheus,” 283.

[^25]: Koch, Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology, 5.

[^26]: Ibid., 5.

[^27]: Robert Skelton, “Imperial Symbolism in Mughal Painting,” Content and Context of Visual Arts in the Islamic World: Papers from a Colloquium in Memory of Richard Ettinghausen, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 2–4 April 1980, by Priscilla Parsons Soucek (University Park: Published for the College Art Association of America by the Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988), 182.

[^28]: Farid al-din Attar, Mantiq al-Tayr translated by C. S. Nott (London: Routledge and Kegan, 1954), 3, quoted in Koch, “The Symbolic Possession of the World,” 552.

[^29]: Koch, Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology, 8.

[^30]: Gauvin Alexander Bailey, “The Indian Conquest of Catholic Art: The Mughals, the Jesuits, and Imperial Mural Painting,” Art Journal 57, no. 1, The Reception of Christian Devotional Art (April 01, 1998): 24–30, 29.

[^31]: Skelton, “Imperial Symbolism in Mughal Painting,” 178.

[^32]: Ibid., 179.

[^33]: Welch et al., The Emperors’ Album, 20.

[^34]: Sumathi Ramaswamy, “Conceit of the Globe in Mughal Visual Practice,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 49, no. 4 (October 01, 2007): 772.

[^35]: Beach, “The Mughal Painter Abu’l Hasan,” 15.

[^36]: McInerney, “Three Paintings by Abu’l Hasan,” 121.

[^37]: Maurice Brock, Bronzino (Paris: Flammarion, 2002), 160.

[^38]: Milo Cleveland Beach, Stuart Cary Welch, and Glenn D. Lowry, The Grand Mogul: Imperial Painting in India, 1600–1660 (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1978), 27.

[^39]: Koch, “The Mughal Emperor as Majnun, Orpheus, and Solomon,” 277.

[^40]: Merriam-Webster, accessed November 8, 2014, http://www.merriam-webster.com/.

[^41]: Lefèvre, “The Majālis-i Jahāngīrī,” 280.

[^42]: Robert Skelton, “Imperial Symbolism in Mughal Painting,” 178.

[^43]: Mary E. Heston, e-mail message to author, November 9, 2014.

[^44]: Preziosi, Donald (ed), The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 133.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Qadi. Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise. Translated by V. Minorskij. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst., 1959.

Alam, Muzaffar, and Sanjay Subrahmanyam. Writing the Mughal World: Studies on Culture and Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Asher, Catherine B., and Cynthia Talbot. India before Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. “The Indian Conquest of Catholic Art: The Mughals, the Jesuits, and Imperial Mural Painting.” Art Journal 57, no. 1, The Reception of Christian Devotional Art (April 01, 1998): 24–30.

Beach, Milo Cleveland. “The Gulshan Album and Its European Sources.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 63, no. 332 (January 01, 1965): 63–91.

Beach, Milo Cleveland. The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court. Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, 1981.

Beach, Milo Cleveland. Mughal and Rajput Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Beach, Milo Cleveland. “The Mughal Painter Abu’l Hasan and Some English Sources for His Style.” The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 38 (January 01, 1980): 6–33.

Beach, Milo Cleveland, Stuart Cary Welch, and Glenn D. Lowry. The Grand Mogul: Imperial Painting in India, 1600–1660. Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1978.

Beckwith, Christopher I.. Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Berlekamp, Persis. Wonder, Image, and Cosmos in Medieval Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Blair, Sheila, Jonathan Bloom, and Richard Ettinghausen. The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250–1800. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Brock, Maurice. Bronzino. Paris: Flammarion, 2002.

Faruqui, Munis Daniyal. Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Fisher, Michael Herbert. Visions of Mughal India: An Anthology of European Travel Writing. London: I.B. Tauris, 2007.

Goetz, Hermann. “The Early Muraqq’s of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir.” East and West 8, no. 2 (July 01, 1957): 157–85.

Hattstein, Markus, and Peter Delius. Islam: Art and Architecture. Cologne: Könemann, 2000.

Heston, Mary E.. E-mail message to author. November 9, 2014.

Jahangir, and W. M. Thackston. The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. New York: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Association with Oxford University Press, 1999.

Koch, Ebba. Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology: Collected Essays. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Koch, Ebba. “The Mughal Emperor as Solomon, Majnun, and Orpheus, or the Album as a Think Tank for Allegory.” Muqarnas 27 (January 01, 2010): 277–311.

Koch, Ebba. “The Symbolic Possession of the World: European Cartography in Mughal Allegory and History Painting.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55, no. 2/3, Cultural Dialogue in South Asia and Beyond: Narratives, Images and Community (sixteenth–nineteenth Centuries) (January 01, 2012): 547–80.

Lefèvre, Corinne. “The Majālis-i Jahāngīrī (1608–11): Dialogue and Asiatic Otherness at the Mughal Court.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 55, no. 2/3, Cultural Dialogue in South Asia and Beyond: Narratives, Images and Community (sixteenth–nineteenth Centuries) (January 01, 2012): 255–86.

Losty, Jeremiah P., and Malini Roy. Mughal India: Art, Culture and Empire: Manuscripts and Paintings in the British Library. London: British Library, 2012.

McInerney, Terence. “Three Paintings by Abu’l Hasan in a Manuscript of the Bustan of Sa’di.” In Arts of Mughal India: Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2004.

Merriam-Webster. Accessed November 8, 2014. http://www.merriam-webster.com/.

Moin, A. A.. “Peering through the Cracks in the Baburnama: The Textured Lives of Mughal Sovereigns.” Indian Economic & Social History Review 49, no. 4 (2012): 493–526.

Preziosi, Donald, ed. The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Ramaswamy, Sumathi. “Conceit of the Globe in Mughal Visual Practice.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 49, no. 4 (October 01, 2007): 751–82.

Richards, John F.. The Mughal Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Robinson, Francis. The Mughal Emperors and the Islamic Dynasties of India, Iran, and Central Asia, 1206–1925. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2007.

Roe, Thomas, and William Foster. The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of the Great Mogul, 1615–19: As Narrated in His Journal and Correspondence. London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society, 1899.

Seyller, John. “Codicological Aspects of the Victoria and Albert Museum Akbarnāma and Their Historical Implications.” Art Journal 49, no. 4, New Approaches to South Asian Art (December 01, 1990): 379–87.

Seyller, John. “The Inspection and Valuation of Manuscripts in the Imperial Mughal Library.” Artibus Asiae 57, no. 3/4 (January 01, 1997): 243–349.

Seyller, John William. Workshop and Patron in Mughal India: The Freer Rāmāyaṇa and Other Illustrated Manuscripts of ʻAbd Al-Raḥīm. Zürich: Artibus Asiae Publishers, 1999.

Skelton, Robert. “Imperial Symbolism in Mughal Painting.” In Content and Context of Visual Arts in the Islamic World: Papers from a Colloquium in Memory of Richard Ettinghausen, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 2–4 April 1980, by Priscilla Parsons Soucek, 177–87. University Park: Published for the College Art Association of America by the Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988.

Smart, Ellen. “The Death of Ināyat Khān by the Mughal Artist Bālchand.” Artibus Asiae 58, no. 3/4 (January 01, 1999): 273–79.

Soucek, Priscilla P.. “Persian Artists in Mughal India: Influences and Transformations.” Muqarnas 4 (1987): 166–81.

Srivastava, Ashok Kumar. Mughal Painting: An Interplay of Indigenous and Foreign Traditions. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2000.

Stronge, Susan. Painting for the Mughal Emperor: The Art of the Book, 1560–1660. London: V&A Publications, 2002.

Turner, Howard R.. Science in Medieval Islam: An Illustrated Introduction. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997.

Verma, Som Prakash. Interpreting Mughal Painting: Essays on Art, Society, and Culture. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Welch, Anthony, and Stuart Cary Welch. Arts of the Islamic Book: The Collection of Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan. Ithaca: Published for the Asia Society by Cornell University Press, 1982.

Welch, Stuart Cary, Annemarie Schimmel, Marie L. Swietochowski, and Wheeler M. Thackston. The Emperors’ Album: Images of Mughal India. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.

|

| Fig 1. . Jahangir Preferring a Shaykh to Kings,by Bichitr. Mughal period,ca. 1615-18. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Instutuion. Prchase. F42.15. |

|

| Fig 2. Jahangir Embracing Shah Abbas. Painted by Abul Hasan, ca. 1618. Opaue watercolor, gold and ink on paper. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. |

|

| Fig. 3. Jahangir Shoots Malik Ambar. Painted by Abul Hasan ca. 1620. Guache on paper. Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. |

|

| Fig. 4. Jahangir Shooting Poverty. Attributed to Abul Hasan ca. 1620-25. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. |

|

| Fig. 5.Celebrations at Jahangir’s Accession, by Abu’l Hasan. From a Jahangirnama manuscript. Mughal period, ca. 1605. Saint Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Science. E. 14,folio 21. |

| |||

| Fig. 7. The Weighing of Prince Khurram. Jahangirnama Manuscript, Mughal period, ca. 1625, bequeathed by P.C. Manuk Esq. and Miss G. M. Coles through the N.A.C.P. 1948.10-9.069. British Museum. |

|

| Fig. 8. Pietatis Concordiae or The peace among the animals according to Isiah, designed by the editor of the Royal Polyglot Bible, Benito Arias Montano, drawn by Pieter van der Borcht, and engraved by Pieter an der Heyden, 1569. |