Madhurima Mandal

Registration No.: 16110622024

Roll No.:24

UG II

History (HIST0302)

Professor: Sajjad Alam Rizvi

September 21, 2017

INTRODUCTION

The fourteenth century of the Christian era marked great changes. There were changes taking place in the social and political scenario. In the west, the middle classes begun to demand and receive, a share of power and in the east, strong centralized empires were established. During this time Islamic rule flourished, as they united the world through trade and commerce. Strong and centralized Islamic empires like the Mongols, Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals were established.

The beginning of the fifteenth century in the

Indian sub-continent marked great changes as the Delhi Sultanate weakened and

the Afghans, who were constant incursions, were looking for an opportunity to

defeat the Sultanate. This opportunity finally came in the form of the First

Battle of Panipat(April 20, 1526), between Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad also know as

Babur, and Ibrahim Lodi, which resulted

in Babur defeating the Lodis thus establishing the Mughal rule in India.

In

the Ottoman Empire, Bayazid I (1389-1402) met his nemesis in the form of Timur,

founder of the Timurid Empire, at the Battle of Ankara (1402). The Ottoman Empire

thus began to generate in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, after it

started losing its territories, however it did not decline before the twentieth

century.

Thus the fifteenth and sixteenth century witnessed great changes in India, as elsewhere in the world, which resulted in the reorientation of the world.

BACKDROP OF THE BATTLE OF

PANIPAT

In the first of the fourteenth century, the

Delhi Sultanate flourished as the Khiljis and Tughluqs carried the banners of

Delhi, far and wide. The Delhi Sultanate was strengthened under the reign of

Balban and Alauddin Khilji. None the less the less the scenario changed in the

second half of the fourteenth century, as the seeds of its decline was sowed.

It all started in the reign of Muhammad-bin-Tughluq (1324-1351). The

controversial step taken by him was the shifting of capital from Delhi to

Deogir, thus making an attempt to bring the entire South India under the direct

control of the Sultanate, which led to serious political difficulties. Many

rebellions broke out in South India like in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. The failure

with the introduction of token currency affected the prestige of the sovereign

further.

Muhammad-bin-Tughluq’s

successor, Firoz Shah Tughluq, was faced with the problem of preventing the

breakup of the Delhi Sultanate. So he adopted the policy of appeasing the nobles,

army and theologians. He extended the principle of heredity to the military.

The witness of the Delhi Sultanate was further aggravated by Timur’s invasion

in 1398. The growing weakness of the Delhi Sultanates, led to the Northern

India, strike their independence.

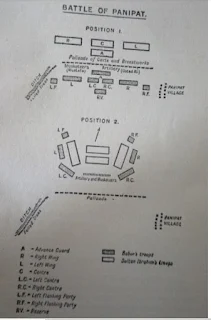

|

Fig.

1

The

political situation in Northwest India was thus, ripe for the Afghans led by

Babur’s entry into India. Ibrahim Lodi’s efforts in centralizing the Empire

alarmed the Afghan chiefs. In 1518-1519, Babur conquered the fort of Bhira;

however he gained nothing from this and returned to Kabul. In 1520-1521, Babur

crossed the Indus and captured the fort of Bhira and Sialkot, but the news of a

revolt, led him redressing his steps and after a siege, he captured Qandahar.

In 1525, Babur’s approach at Peshawar, melted away the army of Daulat Khan

Lodi, governor of Punjab, thus within three weeks, Punjab was captured, leading

him towards the conquest of the entire Indian subcontinent.

Babur met Ibrahim Lodi at Panipat, as he marched towards Delhi. Ibrahim Lodi had a force of 1, 00,000 men and 1000 elephants. Babur’s army had around 12,000 men. This was the First Battle of Panipat which took place on April 20 1526, is one of the most remarkable battles of History as it reoriented the political scenario of the Indian sub-continent.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF

BABUR’S RULE IN THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT

Babur’s lineage could be traced from the two greatest Empire builders in the History- Chengiz Khan (1206-27) and Timur (1370-1405). His legacy proved us the fact that what at most he could be was to be a conqueror, an Empire builder and outshine his name in the pages of History just like his descendants. On his father’s side, he was a direct descendant of Timur, in the fifth generation and on his mother’s side he was the descendant of Chengiz Khan, in the fourteenth degree.

|

Fig. 2

Babur

had grown up in the background where the Timurid Empire weakened and got

divided between the princes. In the wake of a conspiracy against him in his own

dominions, worsened his position as he lost both Samarqand and his kingdom in

Farghana, at the end of the fifteenth century. Babur was thus, left without any

kingdom and had to suffer a great deal as he said, “great poverty and

humiliation”[1].

He tried his luck again at Samarqand, and defeated the Uzbeks but still he was

not strong enough to expel them from Transoxiana. He joined hands with the

Persian army and conquered Bukhara and Samarqand. However he was soon overthrown

from Samarqand, through a series of events, by the Uzbeks. Babur in all these

events had overestimated his ability to retain Samarqand. Nevertheless, it did

have a positive outcome in his career as a conqueror, as he after his failed

expeditions, diverted his attention towards India.

We

often get to know that Babur had a dream of conquering India and that never

went out of his mind. He grew up, listening to the tales of Timur’s exploits in

India, which thus fired his imagination. Babur said that from the time he

conquered Kabul (1504) till his victory in the battle of Panipat (1526), “I had

never ceased to think of the conquest of Hindustan”[2].

His army was not formidable enough to conquer the Indian sub-continent. “But he

was never a man to hesitate because the odds against him were heavy”[3].

With his excellent tactics, most of which he learnt from the Timurids among

which the willing tactics of Tulghuma[4].

Following this victory Babur concluded his account with the description of the

land he just conquered, “although Hindustan is a country naturally full of

charm yet its inhabitants are devoid of grace; and in intercourse with them there

is neither friendly society, amity, nor stable relationship”[5].

Though h also admits of the country’s advantages, “the great advantage of

Hindustan, besides the vast extent of its territory, is the amount of gold,

coined and uncoined, which may be found there. Also, during the rains the

climate is very pleasant. Another advantage of Hindustan is the infinite number

of craftsmen of all professions and industrials which abound in it.”[6]

Fig.3

However,

after the victory at Panipat, he faced some serious problems. After seizing all

the rich treasures of the Lodis, his army men thought that their struggle had

been rewarded an it was time for them to return to central Asia. Babur said

that there was “remarkable dislike and hostility”[7]

between the people of Delhi and Agra and his men. It was probably because of

the fact that Timur’s ransacking and plundering in 1398 was still afresh in

their minds. Thus, Babur took some strict steps to quench the discontent among

his army men and begs. He appealed to them that he did not endure the hardships

just to seize the wealth of then Lodis and return to Kabul, he intended to do

something more. However he also permitted the people to leave who made up their

minds to do so. Thus, Babur was firm in bringing the entire north India under

him and when his determination came to be known to the Rajputs, who previously

thought after seizing Lodi’s treasures and plundering he would return back to

Kabul thus leaving Delhi in the hands of the Rajputs, realised that Babur “was

not an involuntary friend but a conscious enemy.”[8].

The

chiefs like Shaikh Guren, an important chieftain of Kol in the Doab, joined

Babur and he bought some 2000 men, who too joined Babur’s army. Many rebellious

nobles in the east joined him thus strengthening his army further. He was left

to face with two dangers, first was the Rajputs under Rana Sanga and the second

from the eastern Afghans. At the mean time Babur remained at Agra strengthened him

further by organizing his army and their newly acquired resources. His plan was

to reduce the eastern Afghans to submission before him and then undertake a final

expedition against Rana Sanga.

Thus,

the battle between the Rajputs and Babur was inevitable, as the latter as

determined to stay in India. The battle was not between the Rajputs and Babur;

it was between the Rajput-Afghan allies and Babur where the former was joined

by other Rajput kings and Mahmud Lodi, the younger son of Sikander Lodi. It was

basically a political battle, but Babur tried to give it a religious colour to

raise the spirit of the soldiers. He said that it was not a war against the

Rajputs, but a holy war, Jihad. The Battle of Khanwa took place in 1527 and

just like the battle of Panipat; Babur studied the area and made all

preparations in a similar fashion as in the previous battle. The Rajputs were

over confident and it seemed that they did not learn anything from the tactics

adopted by the latter at Panipat. Rana Sanga was proud of his army and

elephants and as usual it attacked furiously on Babur. What Babur observed is,

“swordsmen though some Hindustani maybe, most of them are ignorant and

unskilled in military move and stand, in soldierly counsel and procedure.”[9]

Once again the former was rooted with his unplanned moves and over confident

attitudes. Rana Sanga escaped to Chittor and the grand alliance disintegrated

as quickly as it was built. The battle secured Babur’s position in the Gangetic

doab and led to the establishment of the Mughal emperor which changed the fate

of Hindustan forever.

Fig.

4

After

the Battle of Khanwa, Babur to seal his triumph went to Bayana. However facing

a hot weather he abandoned this decision and instead marched towards Mewat and

Alwar, to bring the local chieftains under his control. An effort was made to

win over the leading Afghan nobles of Ibrahim Lodi which included Shaikh

Bayazid of Awadh. He in order to prove the fact that he had no hatred for the

Lodi family; he gave paraganas worth 7, 00,000 and a place to live in to

Ibrahim Lodi’s mother. But she tried to poison him, thus increasing Babur’s

distrust for the Afghan nobles.

Fig.

5

He

was determined to crush them and at the Battle of Ghaghra (1529), the Mughals

defeated the alliance of the Bengal king and Afghans. He ousted Shaikh Bayazid

from Lucknow and was keen to consolidate his empire. He also captured the

fortress of Ranthambore, surrounded to him by Vikramadit, the second son of

Rana Sanga, which filled him with pride as he felt his dream of subduing India

was nearly done.

Fig.

6

It

was unfortunate enough because Babur did not necessarily have administrative

skills, but he was a great warrior with statesman like skills. However, he

found it necessary to have an administrative plan, which he carried out by

giving the dominance to the great amirs. The consequences of this plan had been

same as always, when monarchy lost authority slowly, allowing the amirs having

total control over the dominance, hence “the throne became the prey of

contending factions”.[10]

However in the reign of Babur, the consequences were not apparent enough, first

because of his prestige as a warrior, and secondly the period during which he

ruled was too short for the consequences

to be apparent.

Fig.

7

Babur was an efficient warrior having founded one of the greatest empires in History, but as an administrator he failed. His treasure has deficit, as he was too generous to distribute all the royal hoards to his soldiers and amirs. Nonetheless the deficit was made with a levy of thirty percent revenue on the great officers. But when these deficits got repeated during the reign of Humayun, it led to financial breakdown followed by revolutions, intrigue and the dethronement of the dynasty. It was Sher Shah Suri, who dethroned Humayun, was a great administrator, and built an administrative machinery based on which Akbar later built his administration.

Babur’s health had gone down by the summer of 1529, when Humayun’s mother Maham came from Kabul to join her husband in Agra. Humayun despite his failures, because of his personal charm and dutiful behaviour, secured his father’s affection more than his brothers. During this time he went to Sambhal to complete the settlement of jagir. But he could not face the hot weather of 1530 and fell dangerously ill. He was bought to Agra and Babur was so grieved seeing his son’s condition, in spite of his own weak health he craved for his son to remain alive and be the next emperor. It is said, “He walked three times round the sick-bed and then exclaimed that he had born away Humayun’s sickness.” After this Humayun recovered from his sickness and Babur died. This is indeed a great sacrifice of a father for his son and this outshined the latter in the pages of history.

LEGACY OF THE MUGHAL

EMPIRE UNDER HUMAYUN

Nasirud-din Muhammad Humayun succeeded Babur and ascended the throne on December 29, 1530 in the city of Agra. Babur’s wakil, Khalifa Nizamuddin, was eager to set aside Humayun and put Mehdi Khwaja, on the throne was married to Babur’s elder sister. Apart from this Babur’s brother, his sons and other Timurid princess were determined to assert their power in India by removing Humayun. So we witnessed an atmosphere of disturbance as the emperor descended the throne. Moreover, the army which compromised a mixed body of people, Uzbeks, Moghol, Persian, Afghan, Chaghatai and Indians were not unanimous in supporting the emperor.

The empire was not consolidated when Babur died and Humayun had entered India since five years but all this time he was busy in military expeditions. The Afghans were again raising their heads, among them the most able was Sher Shah Suri, who already took up arm in Bihar and Bengal during the end of the formers reign. The later was benevolent enough, as its first act after accession, was of assigning Jagir to be held by his brothers. However, this union did not last long as they were plotting to remove the latter from his throne. Kamran, the latter’s brother, showing hostility towards him occupied Punjab and its neighbouring provinces. Humayun defeated the Afghans led by Sultan Mahmud and Shaikh Bayazid. In order to break the Afghan power, marched towards the fort of Chunar, captured it, but was flattered by Sher Shah and thus he withdrew his troops.

Bahadur Shah of Gujarat wanted to avoid a conflict with the Mughals, but with Humayun’s accession of the throne he was convinced by the Afghans and the Timurid princess that the Mughals were not a formidable force as they had been earlier. In the beginning he flattered the latter by congratulating him on the completion of Din Panah. After this he marched towards Chittor in 1535 and assigned important jagirs to the Timurid princess and tried to intrigue Sher Shah against the Mughals by sending large sums of money. Finally he launched a three-pronged attack on the Mughals by attacking Agra, under the force to attack Kalinjar in Bundelkhand, the third attack in Delhi and to create disturbances in Punjab. However the attack failed, after which Humayun conquered both Gujarat and Malwa. However in February 1537, both the territories were lost on account of his lack of orders, to be issued to administer the territories.

After the conquest of Gujarat and Malwa, Humayun was informed of Sher Shah extending and consolidating his influence in Bihar and Bengal. During this period, Sultan Juneid Birlas, the governor of Jaunpur and other eastern provinces and thus, subdued Sher Shah, who after his death, turned to capture Bengal. The Mughals then went to Bengal, set up a government and started for his journey to Delhi. His absence in Delhi, led Sher Shah acquiring Benaras, Chunar and Jaunpur, as he devastated the Mughal possessions till Kannauj and Sambhal. Thus, the Mughals were at great loss as the emperor returned to Delhi and Sher Shah overran Bengal.

Humayun was so obsessed with Mughal superiority, faced Sher Shah in the Battle of Chausa (26 June, 1539) and Battle of Kannauj (17 May, 1540), where he was vanquished. The former’s brother refused to support him and thus, was overthrown by the latter. He planned of going to Sindh, conquer Gujarat and renew his fight with Sher Shah. His brothers plotted to kill him and to save his life after repeated failures he fled to Persia. He was welcomed by the Governor of Seistan. Later, he received news from the Court of Persia, where he was welcomed in a grand manner and encouraged by Shah Tahmasp of Safavid Empire to open the gates of the kingdom subdued by Babur. The Shah assisted him with a large force to expel his brothers out of Kabul, Qandahar and Badakshan. He even marched to Qandahar and captured it. After appointing Bairam Khan, in charge of Qandahar, he proceeded towards Kabul and took over it in 1545. After reuniting with his son Akbar, he left for Badakshan after leaving the latter at Kabul. Seizing the opportunity, Kamran recovered Kabul in 1546 but Humayun returned and sized it again. He also subdued Badakshan, but the former again seized it. In 1551, Kamran reoccupied Kabul but was finally defeated by Humayun.

Humayun in 1554 got information about the revolts and rebellions taking place after the death of Islam Shah, the son of Sher Shah. The Sur Dynasty was facing civil war under Sikandar Sur. Seeing this as an opportunity, he crossed the Indus and occupied northern Punjab and Lahore. Bairam Khan advanced to Jalindher and occupied Sirhind as he crossed the Sutlej River. In the battle of Sirhind, Humayun defeated Sikandar Shah. Humayun occupied Delhi on the holy day of Ramzan and all other provinces fell rapidly in his hand. He planned the administration of his empire, divided it into several grade divisions, each of them having a local capital and a board of administration to direct the local affairs.

Humayun

died shortly after he recovered his empire on 20 January, 1556. He was at his

library while descending the steps, he heard the moizzin (cryer from the

minaret of the mosque), summoning for the evening prayers and he prepared to

sit on the stairs till the proclamation ended. However as he was going to rise,

his foot entangled in the skirt of his mantle and the steps made of marble

being slippery, ‘the stairs in such situations are narrow steps on the outside

of the building, and only guarded by an ornamental parapet about a foot high.”[11]

Thus he fell down heading from the stairs and expired at the forty-eighth year

of his age on 24 January, 1556.

THE COURT UNDER BABUR AND

HUMAYUN

The

government was a foreign ruler who settled themselves by force in the country.

The administration was directed by the king, who was surrounded by Amirs and

great officers. The court was composed mainly of the Begs and Amirs, who held

different province and districts in the empire. In case of both the emperors

the nobles were largely composed of the Turko-Mongol ascent. We do not get any particular information

about the ruling classes during the reign of Babur, since he died soon after

consolidating the empire. Humayun was a magnificent emperor who took care of

his subjects and nobles whom he gave important administrative posts and others

important positions in his court. However it was under Humayun after he

retained his empire with the help of the Safavids that his nobles were mainly

composed of Persian ascent.

There

was no hereditary position except the heads of the tribes and the power

possessed by the head of the tribes was exchanged for the power of a governor

of a province. The ruling classes were not hereditary b but the position of the

ruling class run in the same family. Every village have a jagirdar, who

possessed all the forces and public buildings and people worked under him in

different positions.

All the taxes and revenues are collected by him

and all military, civil and criminal powers were rested with him. So the people

were left at his mercy and the misery of the people was decided by the

character of the jagirdar. Despite the fact, he could not strike the roots as

he was liable to be removed at any time by the king. The people holding high

ranks in the administration comprised the ruling class who possessed a lot of

wealthy. They also had high ranks in the army and even comprised of poets and

men of liberal studies.

The common people were probably the oppressed ones. The extraction of revenue by the government, along with the devastation caused by the hill tribes in the armies left them with very little of their possessions. Oppression, though, united them as they helped each other in group, thus they were “drawn closure by their suffering.”[12] Nevertheless in general, we get little or no information about their daily employment.

CONCLUSION

Babur

had founded one of the largest and influential empires of all times and was

referred to as a ‘Gunpowder Empire’[13]

along with the Ottoman and the Safavid Empires which were contemporaneous with

the Mughals. He inherited his warrior and statesman like skill from the

Timurids and the Mongols, but what he failed in was building a proper

administration, since he died shortly after he fortified his hold in India.

Thus Humayun faced many rebellions and was overthrown. He regained his empire

though he could not bring any gigantic changes in the Mughal administration. It

was Akbar, one of the greatest Mughal emperors, who not only brought the entire

sub-continent under the Mughals but also formed the Mughal administration,

largely based on Sher Shah Suri’s administrative skills. Babur’s dream of

conquering India was carried forward by his successors as the Mughal Empire

became the most influential empire in the world history.

LIST

OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Bibliography

Williams L.F.

Rushbrook, An Empire Builder of the Sixteenth Century, 1918

Chandra Satish,

Medieval India Vol II, 2000

Erskine Williams,

A History of India Under Humayun, 1974

Elphinstone Mountstuart, History of India Vol II, 1841

[1] Satish Chandra, Medieval India Part Two 1526-1748, 8.

[2] Chandra, Medieval India Part Two 1526-1748, 21.

[3] L.F. Rushbrook Williams, An Empire Builder of the Sixteenth

Century, 123.

[4]

a well known Uzbek device, was used against him in 1522 in his encounter against

the Uzbeks.

[5] Williams, An Empire Builder of the Sixteenth Century, 139.

[6] Ibid, 139.

[7] Satish Chandra, Medieval India Part Two 1526-1748, 28.

[8] L.F. Rushbrook Williams, An Empire Builder of the Sixteenth

Century, 141.

[9] Chandra, Medieval India Part Two 1526-1748, 32.

[10] L.F. Rushbrook Williams, An Empire Builder of the Sixteenth

Century, 161.

[11] Mountstuart Elphinstone, History of India (Vol II), 175.

[12]William Erskire, A History of India Under Humayun, 551.

[13] A phrase coined by Marshall G.S. Hodgson & William H. McNeill.