Akbar was born in on October 15, 1542 A.D[1] in Amarkot, Sindh (now in Pakistan). He is often considered the true founder of the Mughal Empire. He reigned over his Mughal Empire in India from 1556 A.D. to 1605 A.D. By now, in addition to Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Sikhism were also religions that the Muslim rulers had to tackle. Akbar stands distinctively from all other Muslim rulers in his policy towards the religions of his kingdom. His policy of inclusivism, religious tolerance, and inter-religious respect and endeavour towards an empire based on unity and equality led to Jawaharlal Nehru calling him the ‘the Father of Indian Nationalism.’[2] As Thapar points out, Akbar ‘won the allegiance of the Rajputs, the most belligerent Hindus, by a shrewd blend of tolerance, generosity, and force; he himself married two Rajput princesses. Rajput princes were given high government ranks, and by 1583 all Rajput states had accepted Akbar as ruler.’[3] His religious policy towards the Hindus was in such a time when religious intolerance was on high and Muslim rule over Hindus was more often of an oppressive kind.[4]

|

| Akbar with people of different religious sects (AI creation) |

It is conjectured that Akbar’s Hindu policy was greatly influenced by the many Hindu wives that he had.[5] Akbar himself was a regular audience of Hindu saints and philosophers. Some consider that a probable influence behind Akbar’s Hindu policy could be Sufism that is said to have inspired him towards a more liberal approach towards Hinduism. Others think that Akbar’s Hindu policy was politically motivated.[6]

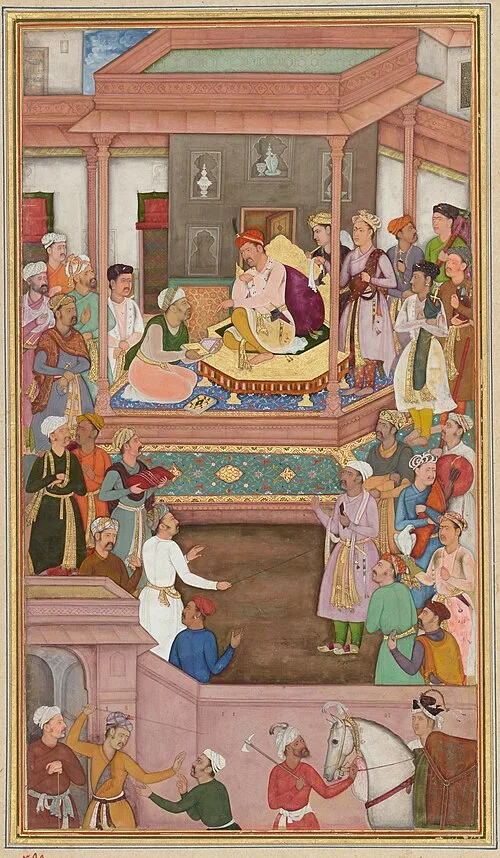

|

| The Emperor Akbar |

In 1562, Akbar banned the forceful conversion of war prisoners. In 1563, he abolished the pilgrimage tax which, immediately, prompted Hindus all over India to construct numerous temples. He also set up a department of translation for the translation of Hindu texts into the Persian language, towards building a common ground for unity between the two cultures. In 1564, Akbar abolished the zazia tax imposed over the Hindus. Earlier on, only the Muslims were treated as citizens. But Akbar gave equal citizenship status to both Hindus and Muslims. His policy didn’t admit political differentiation on the basis of religion. In 1603, he declared a royal decree by which Christians were allowed to convert others.[7]

Akbar opposed child-marriages and encouraged widow re-marriages, which the Hindu law disallowed. In his reign, the Hindus prospered greatly since most Rajputs were given high posts and Hindu warriors formed a large part of the Mughal army. Akbar himself also endorsed much of Hinduism by participating in their festivals.

It is also said that

Akbar learned Hindu doctrines from Hindu Brahmins, Jain thought from

Heera Vijay Suri,

Vijaysen Suri,

Bhanuchandra Upadhyaya, and

Jinchandra; Zoroatrian beliefs from

Dastur Meherji Rana, and Christian doctrines from the Pastors called in from Goa.[8]

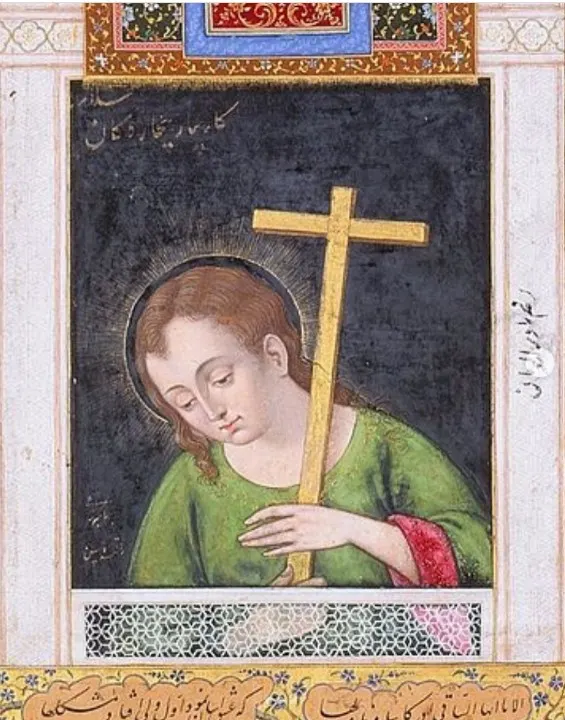

|

| Chester Beatty Library, Dublin ; Mughal Emperor Jahangir with Jesus. |

By the Infallibility Decree of 1579, Akbar became the supreme arbiter over all religious matters of his subjects. By this decree, Akbar became the Imam-E-Aadil and the sole arbitrator of Islamic Law.[9] The decree shows that though the laws were based on reason, the state itself was not separated from religion totally in the modern sense of secularism. However, it must be kept in mind that the above decree, especially in relation to Islam, was in order to prevent Islamic religious authority from tampering with the religious policies of Akbar. This decree prevented fundamental and communal forces from influencing in any way the Emperor’s decisions. By positioning himself above the Islamic religious leaders, getting declared himself as a Judge most beloved on the Day of Judgement, and conditioning his laws to be in line with the Quran, Akbar was able to gain a religious backing for furthering his syncretistic and rational religious policies.

It has been conjectured that these policies of

Akbar grew out of more his syncretistic and pluralistic mind than his adherence to any particular religion. One Portuguese Jesuit of the group that

Akbar had invited to teach him of Christianity when he was in search of truth reported that the Emperor was not a Muslim; in fact, he was skeptical of all religions and was of the opinion that there was not one religion on earth that was specially instituted by God and that there could be found things in any religion that was inconsistent in its own rationality. The Jesuit also reported that

Akbar had found Christianity more interesting than all other religions and that he was close to conversion. He said that there were some in the court who argued that

Akbar was a Hindu who worshipped the sun; some believed that he was a Christian, and others that he was starting a whole new religion (

Din Ilahi) himself. The Jesuit reporter said that there were differences of opinion even among the subjects: some said he was a Muslim; some, Christian; others, Hindu. The wiser men of understanding, the Jesuit continued, believe that he was neither a Muslim, a Hindu, nor a Christian; and that they only considered him a Muslim who was outwardly interested in gaining the approval of all religions.[10]

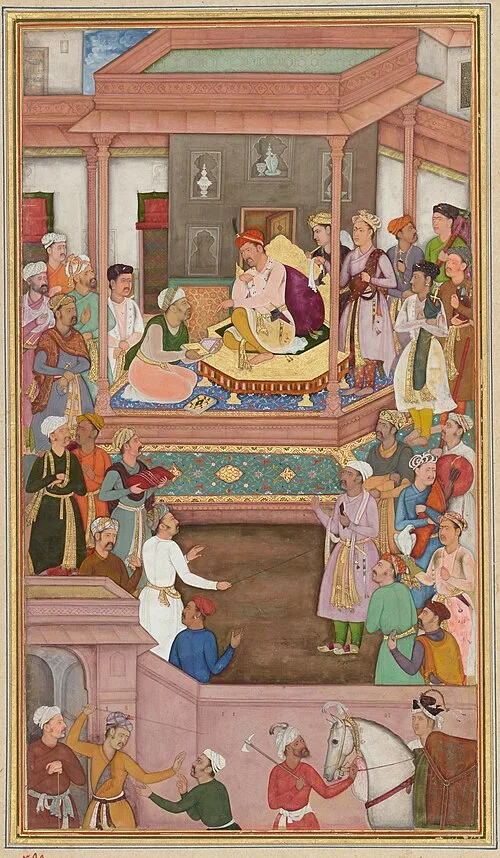

|

| Akbar and the Jesuits. Miniature from Akbarnama by Narsingh |

Akbar’s pluralism is also reflected in the impact Zoroastrianism had on him. In 1578, the Zoroastrian scholar Dastur Meherji declared to Akbar the specialties of this Parsee religion. Consequentially, from 1580 onwards Akbar began to worship the Sun and Fire before his subjects and his courtiers began standing up in respect on the lighting of the evening lights. According to Vincent Smith, it was Jainism that influenced Akbar to stop eating meat and to impose a ban on all kinds of animal sacrifice.[11]Srivastava considers Akbar to be a true rationalist who carried on his investigation into truth in a scientific spirit by which he concluded that sensible men and abstemious thinkers could be found in all religions and that if some true knowledge was thus everywhere to be found, why should truth be confined to one religion or creed like Islam which was comparatively new and scarcely thousand years old.[12] Akbar rejected the Islamic doctrines of Resurrection and Judgement. He also rejected the doctrine of revelation.[13] On the basis of such rational attempts to understand truth, Akbar took to study of different religions and absorbed several ideas from them.

|

A Mughal miniature portraying Abu'l-Fazl, a devoted follower of Din-i-Ilahi, offering the Akbarnama to Emperor Akbar |

Thus, it can be concluded that

Akbar’s religious policies of religious freedom and religious tolerance flowed out of his syncretistic, liberal, rational, and pluralistic way of looking at things. His integrative perspective prevented him from siding with any particular community and thus helped him to inculcate in his subjects a spirit of mutual respect and good will. This pluralistic attitude also grew out of his comparative study of the various religions and people as well as his own belief in the power and value of reason in understanding and judgement. On such grounds, therefore, it can be stated that though

Akbar’s policies did not totally conform to all the elements of modern secularism, they contained the secular seeds of state-sanctioned religious freedom and dignity. His claim for Supremacy over religious matters in a monarchial government that was far removed from the modern concept of democracy and constitutionalism, however, limited his policies only to his period. Later successors, especially

Aurangazeb, reverted more intensively to the methods of fundamentalism, intolerance, and forced conversions. Thus, though

Akbar promoted religious freedom in his own time, he could not provide a mechanism by which his policies could be followed on even after him. This truly shows the importance of a written constitution, a democratic form of government, the separation of powers, and a total separation of state and religion for the future of secularism in any pluralistic context.

Footnotes

[1] Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava, History of India (1000-1707A.D.) (Agra: Shiva Lal Agarwal & Co., n.d.), p. 434.

[2] Laxminarayan Gupta, History of Modern Indian Culture, p.24.

[3] Romila Thapar, Akbar, Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia (Microsoft Corporation: 2001).

[4] Vidyadhar Mahajan, Muslim-Kalin Bharat (Muslim Rule in India) (Delhi: S. Chand & Co. Ltd., 1979), part II, p.103.

[5] Ibid, p. 104.

[6] Ibid, p. 107.

[7] Ibid, p. 108.

[8] Ibid, p. 110.

[9] Ibid, p. 110.

[10] Ibid, p.139.

[11] Ibid, p. 142.

[12] Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava, History of India (1000-1707A.D.), p. 471.

[13] Ibid, p. 471.