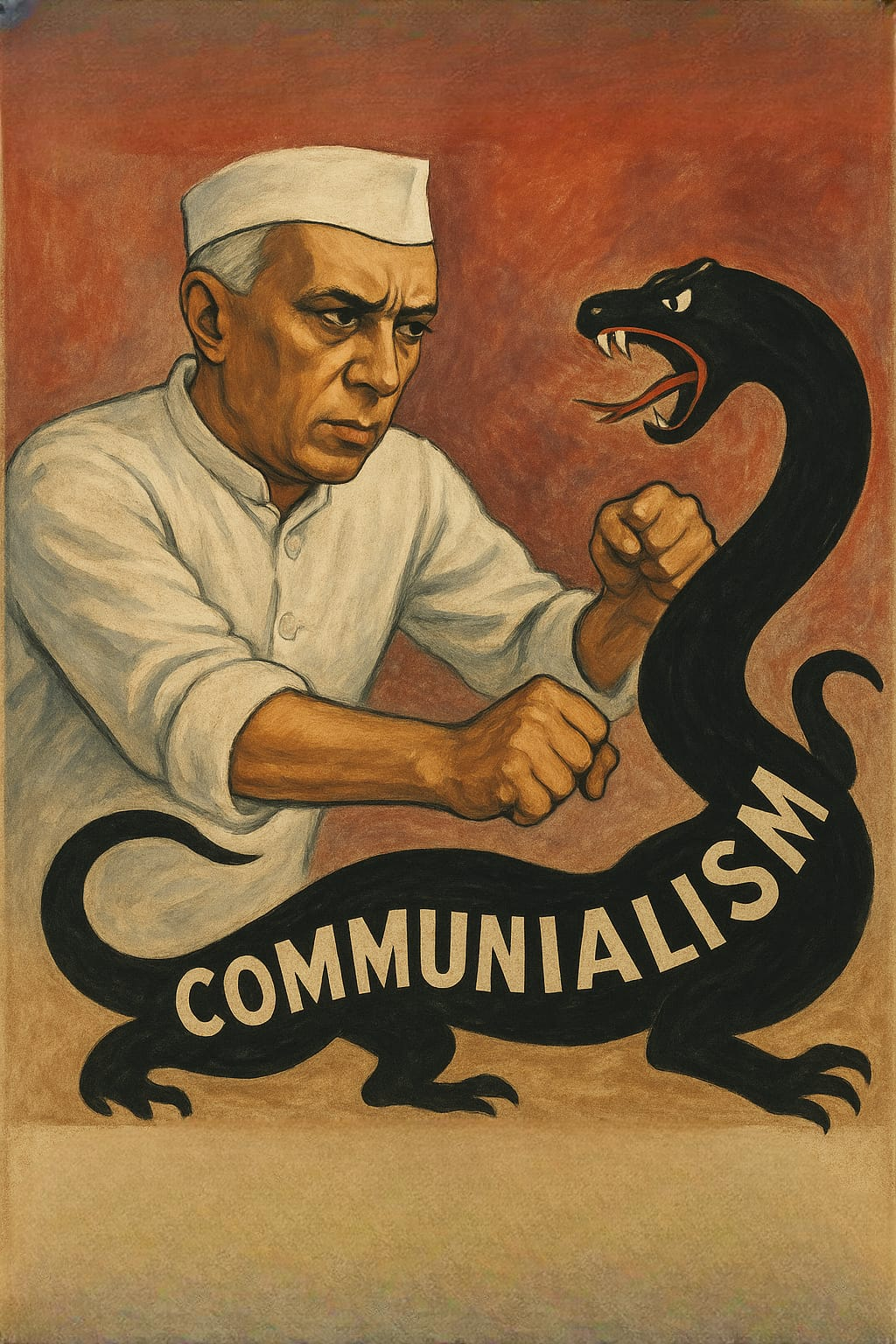

| Title | A Light in the Darkness: Jawaharlal Nehru and Communalism – 1947-50 |

|---|---|

| Author | Neha Munshi |

| Category | Studies about Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Number of Pages | 16 |

| Language | English |

| File Size | 315 KB |

| File Type | |

| Country of Publication | Britton |

| Main Topics | Introduction, the Road to Independence – 1946 Pre-Partition Violence in Bengal and Bihar, Freedom Leads to Violence - September 1947 Communal Violence in Delhi, Post-Independence Onwards – Gandhi’s Death Brings New Dilemma to the Future of India, The Crisis in 1950 and the Nehru-Liaquat Pact, Epilogue,Bibliography |

Summary Note of this Document

The paper describes Nehru as the light that shone during the dark post-partition period with extreme communal riots and violence. A quote from the Svetasvatara Upanishad serves as an overarching theme to the unity in diversity within the Indian traditions and thereby Nehru's commitment as the first prime minister of India to keep the country united. It looks at Nehru's work from 1947-50 when he in the wake of the partition was dealing with the integration of princely states like Hyderabad, Kashmir, and Junagadh, resettlement of twelve to twenty million refugees, and managing relations with a newly formed Pakistan, besides accomplishing the ratification of the Constitution in January 1950 and the Congress's massive victory in the 1951-52 elections (364 of 489 Lok Sabha seats). The paper, referring to Nehru's letters to chief ministers, his private letters, speeches, and interviews, presents a survey of his secular leadership in combating communalism, which kept recurring as a major threat to India's secular fabric.

Pre-Partition Violence:

The Road to Independence (1946)

Direct Action Day was a Muslim League call by Muhammad Ali Jinnah in August 1946 which sparked the Great Calcutta Killings the very same day. The Great Calcutta Killings of 1946 were an unprecedented outbreak of mob violence that got the city burning and led to at least a hundred people being hacked to death, thousands wounded, and vast properties looted and destroyed. It is reported that no major Hindu or Muslim party leaders were arrested, and many leaders were already in hiding.

While the initial Great Calcutta Killings of 1946 only involved mobs of poor Muslims and Hindus, several middle-class groups and organizations joined quickly on both sides. During the same riots, a Hindu mob, allegedly led by the local branch of the Hindu Mahasabharet, killed a Muslim family. In October, the Noakhali (East Bengal) riots were a logical step for the Great Calcutta Killings to continue further, where the original target group was the Hindus. The retaliatory attacks against Muslim villages were in the Patna, Gaya, and Monghyr districts of Bihar where the victims were the Muslim villagers. The three months of violence in Noakhali (Nov. 1946–March 1947) had cowed the population into a state of terror, and millions had fled in all directions. Unlike the interim government under Jawaharlal Nehru which acted immediately and effectively, Gandhi had to go through about five months of on-and-off visits without much success.

The situation in Bihar was different, and the unrest was subdued in less than two weeks after the government had gone in force, and used brute state power, invoked Gandhian ideals and used his personal prestige to good effect, Nehru also went to these areas and declared that he would prevent the riots "over my dead body" and branded communalism as a fire that could consume all the sacrifices the nation had made. Nehru was distressed by the savagery—he counted the dead and saw many Muslims had been killed—and he found albeit briefly in the army fire that killed 400 rioters a very little relief. He combined Gandhian non-violence with tough law enforcement when he mobilized peasants through pledges, Congress workers for rural peace efforts, and students for reconstruction.

|

The situation in Bihar was different, and the unrest was subdued in less than two weeks after the government had gone in force, and used brute state power, invoked Gandhian ideals and used his personal prestige to good effect, Nehru also went to these areas and declared that he would prevent the riots "over my dead body" and branded communalism as a fire that could consume all the sacrifices the nation had made. Nehru was distressed by the savagery—he counted the dead and saw many Muslims had been killed—and he found albeit briefly in the army fire that killed 400 rioters a very little relief. He combined Gandhian non-violence with tough law enforcement when he mobilized peasants through pledges, Congress workers for rural peace efforts, and students for reconstruction.

Freedom Leads to Violence:

September 1947 Communal Riots in Delhi

The violence in Punjab at the time of Partition caused millions of Hindus and Sikhs to flee to Delhi where they inflamed demands for justice and provoked reprisals against local Muslims. Muslims were desperate for refuge during the arson, murder, and riots, and some elite families came poor and in hiding during the night. The government after the situation had calmed down sent troops from the South which were impartial, evacuated Muslims to camps that were safe such as at Purana Qila and Humayun's Tomb, and an Emergency Board was created under Mountbatten to carry out supervision work day and night. Nehru out of his compassion and duty, and despite the personal risks, went to victims to calm them down and restore order. He treated the crisis as war. In a secret cabinet note, he condemned communalism and enquired if India was to remain a composite state of cultural freedoms or become a Hindu or a non-Muslim entity. To his friend Rajendra Prasad, he expressed his disgust at the cruelty and warned that giving up moral standards would undermine the nation's dreams of being great.

Gandhi was fasting for the return of normalcy - a fast which was broken in early January 1948 following the pledge made by 50,000 Delhiites to protect Muslims and trains, and which reflected Nehru's equal-rights spirit. However, the dissatisfaction of the Hindus resulted in an attempt to bomb Gandhi at Birla House.

Post-Independence Onwards: The Death of Gandhi and New Dilemmas (January 1948)

On January 30, 1948, Nathuram Godse, associated with the Hindu Mahasabha and RSS (which did not attend Independence Day and did not accept the national flag), fatally shot Gandhi at a prayer meeting. Nehru, overwhelmed with grief, made a touching eulogy via radio: "The light has gone out... yet I was wrong," indicating Gandhi's lifelong teachings of truth and non-violence as guides out of error towards freedom for India. He invited the eradication of communal venom "not madly or badly, but... as our beloved teacher taught us." Addressing the Constituent Assembly, Nehru promised action against hatred at no risk of governorship worthiness and firmly stated that inaction would be the greatest tribute to the foes of democracy. At Gandhi's immersion in the waters of the Ganges in front of a million in Allahabad, he declared the need to uproot the seeds of hostility, warning that violence leads to the loss of freedom and calling for the path of truth and dharma.

While there was resistance from within the Congress and a rise in post-partition Hindu self-identification—Hindu communalism mirrored that of Muslims—Nehru compared the situation to "a crisis of the spirit" which was harmful not only for Indian and Hindu ideals but for the whole country as well. After the killing, the public unrest targeted the RSS and Hindu Mahasabha office; among measures taken was a government resolution of February 2 banning organizations that incited or supported violence, which led to the RSS ban on February 4 due to alleged involvement in communal terrorism. A resolution accepted by the Congress in December 1948, with the participation of Nehru, disowned both communalism and political misuse of religion.

The Crisis in 1950 and the Nehru-Liaquat Pact

The ban on the RSS was removed in July 1949 following cultural assurances during which Nehru urged caution. East Bengal riots in early 1950 resulted in Hindu exile to West Bengal, and consequent Muslim retaliation and refugee influx. Nehru, writing to his ministers after nearly three years of independence, described India as a volcano, criticizing the retaliatory cycle. The April 8 Nehru-Liaquat Pact, arrived at after rigorous negotiations, committed India and Pakistan to minority protections and thus, to avoiding war and mass exchanges despite the skepticism of Sardar Patel and S.P. Mookerjee (who resigned). Nehru rebutted the "appeasement" charge against the pact, explaining that it was an act of preventing barbarity and encouraging hope, although implementation was slow.

Epilogue: Echoes in Ayodhya and Contemporary Communalism

This paper contrasts Nehru's era with the 1992 incident when the 16th-century Babri Masjid in Ayodhya was demolished by the BJP-VHP-RSS agitation, which claimed it as Ram's birthplace. It was a place where people worshipped together until 1949 when the issue of idols and the closure of the site controlled by Nehru and Patel, who were afraid of riots, was unleashed. The mobilization of the 1990s, which was deeply rooted in the bitterness of partition, led to the outbreak of riots in which more than 2,000 people were killed. Ram ke Naam, a film made in 1992, tells the story of Pujari Lal Das, the priest, who was killed in 1993 for speaking out against the politically motivated campaign that was not only indifferent to Muslim land donations for temples but also ignored the general secular ethos. This paper, furthermore, laments the impotence of the law against such forces and points out Nehru's steadfast speeches, declarations, and personal torment - his warning in 1947 that giving in to communal mentality leads to disaster for the country - as a tragic foil to the present situation of Hindu nationalism, which is deeply rooted as BJP's ascendancy and incidents such as the 1984 anti-Sikh pogroms, the 1990s Kashmiri Pandit exodus, and the 2002 Gujarat riots demonstrate. Nehru's lamp shining through the darkness of the past is a reminder of the continual danger of communalism which is currently undermining India's unity.

Click on the options below to read the full article.

×