The period of Akbar’s rule (1556-1605) has been regarded as one of the most significant and incomparable periods in Indian history in particular regarding with Hindu Muslim interaction. Indeed, Akbar’s success stemmed from his religious policy that based on Sulh-i Kul (universal peace and harmony) between all his subjects regardless with their social, ethical or religious identities. His religious policy was not a sudden event, rather emerged from in the course of time depending on different internal and external factors. The final stage of Akbar’s religious policy, the Din-i Ilahi (Religion of God), was a syncretic religious movement propounded by him in 1582 A.D., was one of the most substantial dimensions of mutual interaction and relationship between Hinduism and Islam. The primary aim of this paper, therefore, is to examine the factors influencing Akbar’s religious policy and to analyze critically Akbar’s Din-i Ilahi by dealing with its basic features and virtues which more or less shaped his attitudes towards other religious and social groups.

Keywords: Akbar, religious policy, Din-i Ilahi, Hindu-Muslim Interaction, the Medieval India

Introduction

After the arrival of Muslim traders in India in the seventh and eighth centuries, interactions and interrelations between Muslims and Hindus have been commenced. In fact the earliest accounts of encounters between Arab Muslims and South Asian Hindus demonstrate a wide range of interactions and mutual relations. Up to today, Muslims and Hindus in many places and times shaped communities in which there were commercial issues, places of collective worship, shared political and economic institutions, and other forms of exchange such as intermarriages. On the other hand, it is clear that at times the interactions have been contentious and violent, yet without understanding the full range of encounters, it is not easy to make sense of either the dissension or the cooperation that compose the fullness of history.

As the historical documents approved the Hindu Muslim relations improved and took many forms during the Mughal/Gurkani1 period (1526-1857). Certain rulers were quite open not to employing and strategically allying with one another but to pursuing deeper engagement and comprehending at the regional, imperial as well as religious level. Such an attitude taken by competent rulers in a measure can be seen as relevant to benefits of dynasty. When both imperial sources and historical records that have been kept by not only Muslims but other adherents belong to different religious traditions, are examined, many samples of intimate interest and genuine attempts can be found (Mahmud, 1949, pp. 31-39). One of the most famous model of such interest and tolerance to other religions is the third Gurkani ruler Akbar, who not only spoke local languages but also was a master of Hindu poets writing in the Indic language of Brajbhasha, which was, along with Persian, the literary language of north India during his period (Busch, 2010, p. 274).

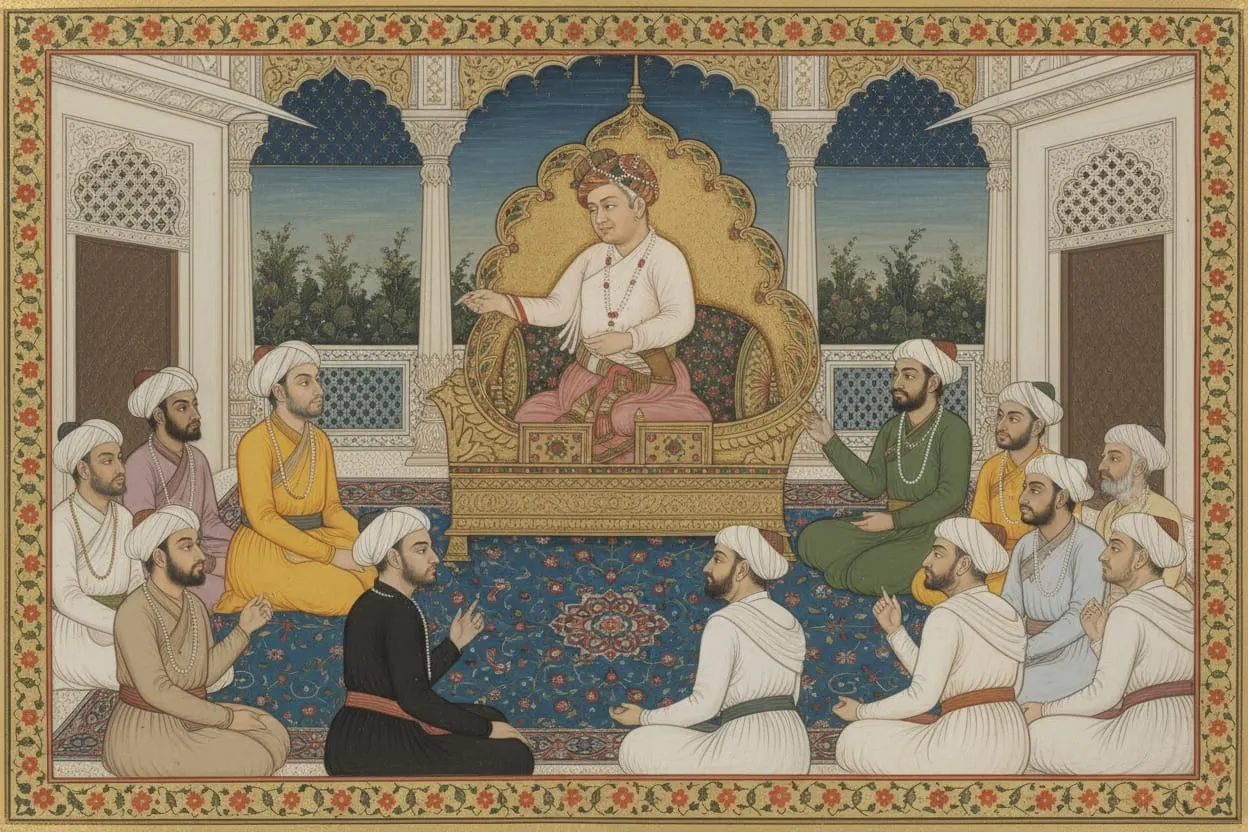

|

| Mughal emporrer Akber painting (clarity enhanced by AI) |

Abu’l Fath Jalal-al-Din Muhammad Akbar, commonly known as Akbar I, literally „The Great‟, was the son of Nasiruddin Humayun whom he succeeded as ruler of the Gurkani dynasty in India from 1556 to 1605 (Smith, 1917). He, as a strong personality and a notable ruler, gradually enlarged his empire to include Afghanistan and nearly the entire Indian peninsula. To unify the vast empire as well as to protect peace and order in a culturally and religiously diverse state, he adopted a distinctive political and religious policy. Akbar first to establish his control over the scattered land then weld his collection of different states, different races and different religions into a whole. For achieving this aim, Akbar firstly improved a religious policy and did his best socio-cultural reforms. Akbar’s religious policy basically based on the doctrine of Sulh-i Kul which means universal peace as well as tolerance for every individual. His religious policy did not discriminate other religions and focused on the ideas of peace, unity and tolerance. Akbar accepted all his subject equal regardless with their religious identities and cultural backgrounds. Akbar considered himself the ruler of all of his subjects, including Muslims, Hindus, and followers of other faiths. For this purpose, he firstly fulfilled various significant implements regarding with religious social, imperial and political issues which had an important role in the development of his religious policy and thoughts (Rizvi, 1975, p. 409).

Factors Influencing Akbar’s Religious Policy

The development Akbar’s religious policy in the course of time was a result of his interaction with not only Muslim society but other religious groups as well as local eminent leaders and rulers. In this context, the religious policy of Akbar was one of the most liberal exponent of the policy of toleration among all Muslim ruler in India. However, his religious views wet through a process of slow evaluation and was effected by internal and external factors. From his childhood, Akbar had come in contact with Islam and in particular Sufism. On the other hand he was educated by some scholars who were the follower of Shia tradition. Akbar’s childhood tutors, who included two Irani Shias, made an important contribution to Akbar’s later inclination towards religious tolerance. Akbar from his early age, therefore, exposed to Sufism and Shia doctrines (Habib, 1997, p. 81).

Akbar’s Rajput views and his contact with Hinduism, on the other hand, made an impression on his imaginative mind. Meanwhile, the bhakti movement had created a new atmosphere in India. As a result of this movement, a great deal of rulers in various parts of India adopted a more liberal policy of religious tolerance, attempting to set up communal harmony between Hindus and Muslim from the beginning of fifteenth century. These liberation and quality songs sung by the teachers and popular gurus of the bhakti movement such as Guru Nanak, Kabir and Chaitanya. This outstanding and effective ideas of bhakti leaders have also impacted on development of Akbar’s religious attitudes towards others (Chandra, 2007, p. 253). Moreover, in the process of improvement of his religious discourses and ideas other religious traditions and their imminent leaders such as Christian missioners and Jainist monks had an important role (Siddique, 2001, p. 109). Therefore, in order to comprehend his unique religious policy, which possesses some important stages like the Din-i Ilahi, and to carry out a critical evaluation on his religious policy the factors impacted on his mind should be firstly analyzed.

The Impact of Muslim Ulamas and Shias

It is known that Akbar, whose parents were follower of the Sunni Hanefi way of Islam (Habib, 1997, p. 80), was firstly effected by his religious environment and background. In particular the attitudes of narrow minded as well as world seeking Muslim ulamas had an important role to shape of his religious mind and policy. His early days were spent in the backdrop of an atmosphere in which liberal sentiments were encouraged and religious narrow-mindedness was frowned upon (Chandra, 2007, p. 253).

One of the most significance Islamic leader of that time, Imam Sirhindi, states also that the world seeking ulama of the reign of Akbar were greatly responsible for misleading Akbar from „sirat-i mustaqim‟ which means the true and right path. According to him, their intention was to attain worldly power, prestige and honor from the people and ruler of time (Ahmad Sirhindi, Maktub No. I/3).

Being dissatisfied with the world seeking and narrow minded ulama, Akbar turned his face towards the spiritual leaders of his age. However, in his time except a few models almost all Sufis were effected by doctrine of unityism, namely “wahdatu-l wujud” (unity of existence). The defenders of this philosophy damaged the essence of Islam by arguing different views against the Quran and Hadiths. Akbar voluntarily or not influenced by this kind of so called ulamas and often he discussed with them like Shaikh Tajuddin, regarding Sufism lonely at nights. For instance, Shaikh Tajuddin due to his idea of „wahdatu-l wujud‟, accepted that to prostrate before Akbar was nothing but prostrating Allah (Badauni, II/259). Furthermore, such an idea also impacted on Akbar’s views that is „to worship Allah, there are many ways and the foundation of each religion is on the truth‟ which is one of the main features of the Din-i Ilahi movement (Hussain, 1957, p. 57).

On the fulfillments of this kind of Sufis, Imam-i Sirhindi mentions that most of the ignorant Sufis of this period were like the world seeking ulama, their contaminating misdeeds had been contagious (Ahmad Sirhindi, Maktub No. I/47). Thus it is clear that influence of so-called spiritual Sufi leaders became a chief cause of the weakening the faith of Akbar in the commands of Islam. With reference to status of true, orthodox and sincere Muslim ulamas in the court, mostly their voices and valuable explanations about religious issues was mostly ignored and their power diminished. Most of them were alienated by those who planned to weak their impacts on Akbar and society. As a result of such an attitude the real Muslim ulama, like Shaikh Badr ud Din, had to leave the court (Badauni, II/212).

As a member of Sunni Muslim tradition through his family Akbar observed the external forms of Sunni faith for a length of time. But in particular his meeting with the liberal views of Shaikh Mubarek and his two sons Faidi and Abul Fadl, was also another important effective factors on the embodiment of Akbar’s religious policy. Through Shaikh Mubarak, Akbar concentrating all powers, temporal and spiritual, into his hand and regarded as „imam-i adil‟ just king, and supreme authority in all respects (Brown, 1930, 4/18).

Shaikh Mubarak and his sons Abul Fadl and Faidi all were a very clever and members of Shia community. Abul Fadl in particular, had intimacy with Hakim Abul Fath and Mulla Muhammad Yazdi, who were strong Shia by faith (Badauni, II/263). The writer of Muntakhabut Tawarikh indicates that Mulla Muhammad Yazdi in his speeches in the court emphasizes on Shias doctrines by ignoring and accusing “Ahl-i Sunnah wel-Jama‟at”

as despicable. Through their views the importance of “wahiy” (revelation to Prophet Muhammad) and basic Islamic beliefs such as faith in observance of five time prayers and the fasts of Ramadan was shaken. Just the reason, thus, was accepted by these Shia thinkers as the alone basis of religious by excluding revelation (Badauni, II/211).

It is clear that under the influence of Shaikh Mubarak and his sons Akbar cut the root of Islam. It is understood from the historical sources that specially due to his influence of Abul Fadl, was one of the famous learned persons of India, Akbar was deviated from the right path of Islam in some respects. On the one side the power of ulama was completely shatter and on the other, same new beliefs which were against the code of Islam became so rampant (Siddique, 2001, p. 96).

Impacts of Other Religous Groups

Akbar’s a special inclination and sympathy for the society of various social identities such as Hindus, Cayinist, Buddhists and Christians as well as a close interaction and association with religious leaders like Brahmins, missionaries, monks and priests was one of the other important factor on the development of Akbar’s religious policy, the Din-i Ilahi, of which main character was based on a huge tolerance to all kinds of religious systems (Badauni, II/161).

Akbar come into close contact with Hinduism because of his regular meetings and discussions with Hindu leaders. Thus he impressed by their strong philosophical solution on topics like nature of man, creation of world and existence of god and then he ordered to translate Hindu religious literature and history into Persian.2 Akbar’s deeply intimacy with Hindus, especially with Raja Birbal and some converted Hindus like Bhavon played a significant role to mislead him from the orthodox way of Islam (Badauni, II/257).

As cited in the Aini-i Akbari due to frank interaction with the both Hindus and Hindu-minded Muslims, Akbar was influenced theory of “samsara” (transmigration) which was the main religious doctrine of all Indian religions (Abul Fadl, 1948, III/303). By the impact of „bhakti‟ thinkers, who particularly emphasized on devotion on Hindu gods like Rama and Krishna, Akbar was also appreciated the value of Hindu gods and goddess. He made some coins in which pictures of Ram and Sita were engraved (Aslam, 1969, p. 119). Besides it is stated in the historical sources that once Akbar in a marriage ceremony observed some rites which were customary among the Hindus (Badauni, II/341). Due to such practices which were observed by Akbar, some prominent Brahmins acknowledged Akbar as an important figure and even an incarnation of god due to his implements for the welfare of both Hindus as well as Hindu religion. To reinforce their views on Akbar Brahmin utilized from some Sanskrit verses in which he was depicted as a hero (Badauni, II/324-25; Busch, 2010).

Akbar’s religious policy based on not only respect all people but lovely attitude towards all kinds of existence including animals and planets and so on. In this regard along with Hindu religion Akbar was also influenced by Jainist doctrines like “ahimsa” which teaches principle of non-violence that is cause no injury and do no harm any living entity (Unto, 1979). Akbar firstly met with Jains in Agra where became a great center for them during the sixteenth century. Later on, after his marriage with the princes of Ambar, he obtained more opportunity to meet and know about Jain beliefs and tradition (Ashirabadi, 1962, p. 262). Being influenced by Jain monks and teachers like Hiravijaya Suri, Akbar abandoned eating meat, garlic and onion for himself (Ashirabadi, 1962, p. 265).3Therefore it is clear that Akbar’s removing of meat and the prohibition of injury to animal life, were basically because of the influence of Jain thoughts (Prasad, 1974, p. 372).

In the process of evaluation of Akbar’s religious policy, in particular declaration of the Din-i Ilahi, his inviting the Christian missionaries to his court and discussion with them had played a dominant role. From A.D. 1580 to A.D. 1605, they came from Goa to the imperial court, in the hope of conceiving the emperor, to introduce Christian religion in his domain. Akbar like other religious groups granted for such missionaries interviews, treated them with kindness and showed interest in their religious doctrines and explanations (Prasad, 1974, p. 301).

Even though the missionaries could not achieve their real purpose fully, it is not difficult to assert that Akbar was effected by their ideas to a great extent. It is evident from the historical records that as a result of Christian impact, Akbar commenced to interrogate the Quran and Prophet in some aspects. Specially some scholars declare that Akbar’s new discourse there is no God but Allah; Akbar is the Caliph of Allah‟ and the using of the statement of „in the name of Jesus Christ‟ instead of “in the name of Allah, the Kind, the Merciful” in Parsian Gospel translation was a result of Cristian influence (Badauni, II/269-314).

From the reports of some Christians who lived at the time of Akbar it is understood that under the reign of Akbar the using of names of Prophet of Islam like Ahmad, Muhammad and Mustafa was diminished and the role of Prophet in the development of Islam was critically discussed like Christians did in their theological fields. Beside this such historical data demonstrate that some place where sacred and valuable in the side of Islam were damaged or destroyed (Makligon, 1932, p. 48) which state also cited by Imami Sirhindi in his letters (Ahmad Sirhindi, Maktub No. II/92).

Apart from the Christianity impact, the other important reason for Akbar’s abjuring Islam was his marriages with ladies or daughters of Rajput rulers. To treat well the Rajputs, Akbar followed some Hindu customs like forbidden of cows, giving of “darshan” (vision) to his subjects and observing some Hindu festivals as well as ceremonies along with the Rajput women. Therefore, it is clear that, even though Akbar firstly planned to preserve and strengthen his vast state by connecting with Hindu Rajputs through their ladies or daughters, he was naturally influenced by these Rajput spouses which lead to practice some Hindu ethos and to break away from essence of Islam (Nadwi, 1982, IV/101). Hence the emergence of Akbar’s unique religious policy based on the principle of tolerance and respect to every each soul and particularly declaration of the Din-i Ilahi was not a sudden decision or development. It came out step by step in the course of time by influencing from Islamic and mostly non-Islamic factors which were dealt with above. Here to comprehend Akbar’s Din-i Ilahi, some earlier basic stages of his religious policy should be examined.

Basic Stages of Akbar’s Religious Policy

The close interaction with Muslim environment and other religious and political leaders influenced on Akbar’s political and social attitudes towards all his subjects. This process also shaped his religious views to others. It means the religious conditions of India at the end of the sixteenth century, in which Akbar lived as a strong figure among people of the peninsula, had an important role in this process. The emergence of Akbar’s religious policy, therefore, was not the sudden outbreak of an idea. Its growth was spread over the years. Akbar’s religious policy could be divided into four stages which are respectively opposing to some traditional practices, “Ibadat Khana” (house of worship, gathering for searching/realization of the Truth), “Mahzar” (the infallibility decree) and “Din-i İlahi” (religion of God). Before the analyzing of the Din-i Ilahi, main aspects and features of the earlier stages should be stated to understand Akbar’s progressing religious mind in the course of time.

Akbar in order to gain supports of other religious and social groups asserted newly ideas and enforced some innovations in both religious and imperial fields. He gave up some traditional Islamic implements committed by either Muslim rulers or theologians on non-Muslims. For instance, Akbar took the most revolutionary step in 1564 by granting religious freedom to Hindus by abolishing „jaziya‟, which was a poll tax, charged from the Hindus in their capacity as “zimmis” (Rizvi, 1975, p. 69). He also removed all restrictions on the construction and maintenance of Hindu temples, churches and other places of worship. Akbar did not discriminate between individuals on the basis of religion or caste instead, he wished to become an impartial rule to whom all people, Hindus as well as Muslims, respected (Rizvi, 1975, p. 156). Such kinds of fulfillments carried out by Akbar should also be regarded as a result of impacts of internal and external factors on Akbar’s mind.

Akbar implemented his religious policy that depends on tolerance and peace, by means of performing different innovations or commitments. He believed that misunderstanding and ignorance in matters of religion caused to discords and conflicts. After evaluating his both socio-cultural and religious-philosophical accumulation, Akbar desired to understand the principles of his religious ideas. On the other hand, driven by a strong desire for truth and knowledge, passionately interested in the mystery of the relation between God and man, he promoted at his court religious debates on a very large ground. From this point of view, he erected a building at Fatahpur Sikri, early in 1575, entitled “Ibadat Khana” (house of worship), in which regular religious discussions were held on Thursdays evenings (Abul Fadl, III/113-119).

In Akbarname the explaining of emperor on building of the “Ibadat Khana” was cited as fallows:

I have organized this “majlis” (gathering) for this aim only that the facts of every religion, whether Hindu or Muslim, be brought out in the open. The closed hearts of our (religious) leaders and scholars be opened so that the Muslims should come to know (essentially) who they are. Because most of them unfortunately are unaware about their religion... (Abul Fadl, Akbarname; Rezavi, 2008, p. 197).

When building “imarat” (complex) was completed in 1576 (Badauni, II/200), in the earlier stages discussions and assemblies were confined to Muslim theologians then Shia ulamas also were included. However, such weekly meetings were interrupted at times and they were regularly resumed in 1578. It is regarded that after this date, 1578 onward, theologians of many faiths and sects attended in the “Ibadat Khana” discussions (Rizvi, 1975, pp. 125-28).

Sunnis and Shias Muslim, Christian, Jainist and Hindu theologians who assembled together in the „Ibadat Khana‟, discussed the rational and traditional methods of discourse, travel and histories and each others prophecies in here. They expanded the field and scope of discussion by arguing their different religious and social thoughts. In this process each of them not only intent to testify his own argument or assertion but demanded to the propagation of his school, tradition or sect in which he grew up (Syed, 2011, p. 406). In this sense it is understood that main object of emperor‟s was to search the truth and reliable and reasonable knowledge.

As a result of religious discourse or disputations held at the “Ibadat Khana”, not only Akbar’s belief in the orthodox Sunni Islam declined but the value of orthodox Sunni mullahs (local Muslim clerics or leaders) who were holding predominant position in the state politics, was lowered. Along with the discussions in the „Ibadat Khana‟, some issues developed in this time, in particular close relationship with Shias, Akbar concluded that

their authority also should be decreased. The first step toward curbing the power of the ulama, he abolished the “waiz” (the head priest) of the Jami Masjid at Fatehpur Sikri and mounted himself as the pulpit. Then read the “khutba”, a religious sermon given on Friday prayers in the masjids by imam, in his own name (Badauni, II/268; Nizamuddin, 1936, p. 342). Akbar went ahead with his plans to reduce the power of the mullahs in the state politics, even though the they criticized or rejected his attitudes (Majumder, 1949, p. 452; Siddique, 2001, pp. 78-79).4

This attempts led to a proclamation, called the “Mahzar” in September 1579. It was prepared by Sheikh Mubarak, and signed by almost all the prominent Muslim theologians. It recognized Akbar in his capacity as the just monarch, to be the “imam-i-adil” (supreme or final interpreter of Islamic law). The “Mahzar” declared Akbar to be higher in rank than the “mujtahids” (the interpreters of Islamic law) (Rizvi, 1975, p. 155). According to some scholars like Mehta (1984) declaration of the „Mahzar‟ did not enable to a religious power to offer a new religious law. Hence Akbar was not permitted by the „Mahzar‟ to violate the fundamental principles of Islam.

|

| Akbar in his royal court (AI creation) |

In the process of approval of the “Mahzar”, Shaikh Mubarak and his sons have possessed an effective role. Therefore in this process the Shia ideas have mostly influenced Akbar’s mind. Shias, under the cover of the so-called infallibility decree, established Akbar as “imam-i adil” (Badauni, II/271-2).5 In other words according to the infallibility decree, Shaikh Mubarak regarded Akbar as the supreme or final interpreter of Islamic law. It is not forgotten here that according to Shia faith, in presence of a caliph, it is possible to be an Imam. The real intention of Shaikh Mubarak by declaration of the “Mahzar”, was to make Akbar as “imam-i adil” and thereby to establish him as a supreme head of all Muslim world and in all respects (Aslam, 1969, p. 106). Consequently the infallibility decree had also played an important role in the development of Akbar’s religious policy and specially declaration of the Din-i Ilahi.

Din-i Ilahi and Its Basic Features

The appear of the Din-i Ilahi should be regarded as the final stage of Akbar’s religious policy. In other words the first three dominant stages have led to reveal of the Din-i Ilahi. Along with Akbar’s earlier stages of religious policy which mentioned above, his perception and thought on Islam must be considered to carry out a proper assessment on the Din-i Ilahi. At the time of Akbar’s reign there was a strong negative discourse about Islam. In this context some eminent people of that time argued that Islam with its own entire aspects was not a valid religion until the day of judgment. As Badauni writes: “According to Majesty, it was settled fact that the one thousand years since the time of the mission of the Prophet, which was to be the period of the continuance of the faith of Islam, were now completed, which he treated in his heart” (Badauni, II/327). After persuading with this idea, it was not so difficult to Akbar to change and design ordinances of Islam. The outcome of his deliberations was the Din-i Ilahi in the beginning of 1582 (Siddique, 2001, p. 115).

The term “Din-i Ilahi” was used by Badauni in connection with a declaration which Mirza Jani Beg, ruler of Tattha, was said to have signed as follows: “I, so and so, do voluntarily, liberate and dissociate myself from traditional and imitative Islam which I have seen my fathers practice and heard from the speak about, and attend the Din-i Ilahi of Akbar acknowledging the four degrees of devotion, which are the sacrifice of property, life, honor and religion” (Badauni, II/304). On account of this declaration, scholars have put forward different explanations and comments. Mostly it is accepted that this declaration signed by governor of Tattha does not

refer to refusing of Islam in all its phases. On the contrary it particularly emphasizes on liberation and disassociation from traditional and imitative Islam (Rizvi, 1975, p. 392). Though Akbar started to conceiving his orthodox noble to abandon “taqlid” but it also do not ignore that in this process he at times damaged to essence of Islam and undervalued some essential Islamic values.

The disciples, member of the Din-i Ilahi movement called also as “illahias”, were also required to sign a same contract of which general frame was shaped by earlier declaration assigned by Mirza (Badauni, II/314). On the other hand Akbar used to accept disciples to his faith with a formula of testimony that “there is no God but God, Akbar is the vicegerent of God” (Badauni, II/273). It is understood from Badauni’s writings that due to fear of public controversy its use was restricted to a few people in the court (Ibid). Even though some scholars like, Siddique (2001) comments such a point as “the disciples cited this formula only in Akbar’s presence” (p. 406), it is, however, clear that such a new formula did not approve by the large community.

One of the other basic implement of disciples of the Din-i Ilahi was greeting each other with the words like “Allahu Akbar and Jalle Jalaluhu” (exalted be his glory) on seeing each other (Badauni, II/356). This rule is intended to keep and to remember the God in mind in every time and to remind men to think of the origin of their existence. Another distinguishing feature of this movement that each disciple of the Din-i Ilahi should prepare a dinner during his lifetime. This rule differed from the classical Muslim and Hindu customs according to which such a dinner generally would have had to organize after a person‟s death. Beside this each member is to give a party on the anniversary of his birthday, and bestow alms in order to prepare provisions for his next life. The struggle to abstain from eating meat was another outstanding rule of members of the Din-i Ilahi. In this sense disciples should not benefited from the same vessels used by fishermen, bird-catchers and butchers. They should not also live together with pregnant, old, and barren women; nor with girls under the age of puberty (Abul Fadl, I/110; Blochmann, 1939, pp. 175-176). This kind of rules and accounts mentioned above demonstrate that disciples were not initiated indiscriminately, and that there was strict checking before access to this religious structure.

According to Mehta (1984), the Din-i Ilahi was a social religious association of the like-minded intellectuals who had transcended the barriers their orthodox religious beliefs and practices. As a result of his religious policy Akbar never compelled anybody to adopt this movement although it would not be difficult for him to do so. It is also clearly mentioned in the rapport of Abul Fadl. According to him the total number of the member of the Din-i Ilahi was not so much. On the other hand it is known that this religious movement could not attract the masses and it ended with the death of Akbar (Rizvi, 1795).

The principles of the Din-i Ilahi was indirectly mentioned in Dabistan-i Mazahib.6In the book this chapter entitled as „Ilahiya Beliefs‟ was divided into four sections. Second section deals with a huge religious discussions between Sunnis and Shias as well as other religious groups such as Jews, Christians and Hindus held in the presence of Akbar. However, there is not enough evident whether this kind of discussions concerned are the “Ibadat Khana” debates. End of the a long discussions between religious leaders it is concluded that salvation is to be achieved only by the knowledge of Truth and by fallowing the precepts of the “Great Namus”, i.e. reason (Rizvi, 1975, pp. 411-12). Renunciation and non-attachment of the world; avoiding from lust and sensuality; refraining from adultery, deceit, oppression, unethical traits, intimidation, foolishness; and emancipation from punishment of the hereafter and doubts about the Truth are all dependent upon obeying the ten virtues. After giving this crucial remembrance the ten virtues of the Din-i Ilahi cited as follows:

(1) Liberality and beneficence; (2) Forgiveness of the evil doer and repulsion of anger with mildness; (3) Abstinence from worldly desires; (4) Care of freedom from the bonds o f the worldly existence and violence, as well as accumulating precious stores for the future real and perpetual world; (5) Wisdom and devotion in the frequent meditation on the consequences of actions; (6) Strength of dexterous prudence in the desire of marvelous actions; (7) Soft voice, gentle words, pleasing speeches for everybody; (8) Good treatment with brethren, so that their will have the precedence to our own; (9) A perfect alienation from creatures and the material world, and a perfect attachment to the Supreme Being; and (10) Dedication o f soul in the love o f God and, very close a union with God, the preserver of all, that as long as the soul may think itself with the Merciful One until the time of separation from its worldly body (Dabistan-i Mezahib, 1904, p. 322).7

Akbar’s religious policy, in particular the Din-i Ilahi, was based on a universal peace and religious freedom for his all subjects regardless of their religious or ethnic identities. While Akbar set fort the Din-i Ilahi he asserted that because of lack of religious freedom and tolerance the Din-i Ilahi was established in this process while Akbar criticized some Muslim ulama due to their limited understanding about Islam itself as well as others religious thoughts. On the other hand he accused Islam arguing that its validity has already ended and and its tolerance to all humanity was not so much comprehensive. In this sense Akbar underestimated the value of Islam in some respects. However, such a view on Islam was incorrect and it was caused not only because of limited knowledge on Islam but influenced mind from other religious systems and traditions. Therefore it should never ignored that this kind of arguments or humanly discourses on religious freedom and tolerance have already established and mentioned in Islam.

For instance, Muhammad (pbuh) describes Muslims in his saying, “A Muslim is he/she from whose hand and tongue the Muslims are safe” (Al-Bukhari, Iman, 10). Islam’s purpose is to make this world a place where all beings are peacefully protected. From the Islamic point of view, killing a human being unjustly is as grave crime as slaying the whole of humanity (Al-Maidah, 5/32). In Quranic perspective one person‟s life is equal to the lives of all human beings. Hence, equally, saving one‟s life is regarded as being same as saving the lives of all people. Islam, hence, does not permit war to be undertaken in order to compel people of other religions to convert to Islam. There is no assert in Islam to make the entire world completely Muslim. “There shall be no compulsion in acceptance of the religion. The right course has become clear from the wrong” (Al Baqara, 2/256).

The basic sources on Akbar’s Din-i Ilahi often indicate the example of Birbal, a Hindu voluntarily joined to the Din-i Ilahi, to demonstrate Akbar’s religious tolerance and freedom (Lal, 1966, p. 242). Through this specific model it is suggested that Akbar made no attempt to use the authority of the state to spread his religion. Despite the fact that such an attitude verified the indulgence of emperor, it should not be neglected that this was not a new foundation or the first fulfillment committed alone by him. As seen above, tolerance for all human being is one of the main core principal of Islam and it has already ordered in various verses of Quran. On the other hand as Siddique (2001) stated that such a person had played an important role to mislead of emperor from orthodox Islamic tradition (p. 97).

Akbar, probably, became aware of this Islamic principles and values in which he brought up until the a long year. As the historical documents revealed, however, Akbar was influenced from Indian culture and other religious groups more then his religious background that is Islam. Therefore when he declared his religious ideas, Akbar at times attempt to differ from some Islamic concepts that is why he was criticized by many Muslim theologians. Nevertheless by analyzing virtues of the Din-i Ilahi it is reasonable to declare that indeed Akbar benefited from basic sources of Islam, Quran and at times Sunnah, when he built his religious thoughts. When he criticized some Muslim ulamas because of their intolerance and unconsciousness attitudes, Akbar also referenced to “tahqiq” (sincere) belief of Islam. Even though Akbar introduced some implements against Islam, he continued to hold in high regard many Islamic institutions and utilized them when he set forth his religious thoughts. Both mutual interaction as well as close resemblance between Islamic values and Akbar’s religious ideas, however, were deliberately or not overlooked by some scholars who had bias or limited knowledge on Islam.

Conclusions

Akbar, an outstanding emperor of Gurkani dynasty, is considered one of the most important figure in the field of Hindu Muslim interaction in medieval period of India. As soon as he came to the throne, Akbar accepted himself as the impartial ruler of his all subjects. In this context he managed all the Indian people irrespective of their castes, creeds and religious beliefs and practices, into homogeneous society. Hence his religious policy was based on Sulh-i Kul, universal peace. Along with Akbar’s association with Sufis and Shias from beginning of the his early age, his intimate contact with so many people professing different faiths surely had a great impact on the development of Akbar’s imperial and religious policy. His religious policy, therefore, was not suddenly broken out; on the contrary, it was improved in the process of time.

The framework of Akbar’s religious thoughts, particularly the Din-i Ilahi, formulated by him in end of the sixteenth century, was depended on eclectic selection and ethical system. Though the appeal and influence of the Din-i Ilahi were limited and could not find opportunity to survive after Akbar, as the historical evidence demonstrate that Akbar’s religious movement more or less weakened the power of Islam even for a limited time and criticized by many orthodox Muslim theologians. Basic elements of this religious movement were essentially taken from Islam and Hinduism, yet some others were also drawn from different religious systems such as Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Jainism. However, some scholars voluntarily or not neglected the impact of Islam on Akbar’s social and religious attitudes towards others without considering the innovative discourses of Islam on religious freedom, tolerance and equality which were already ordered in the main sources of Islam more than nine hundred years before Akbar brought up.

References

Abu’l Fazl. (1873-87). Akbar Nama, 3 Vols. Calcutta, (Trans. H. Beveridge). Calcutta, 1897-1921. Abu’l Fazl. (1892). A’in-i Akbari, 3 Vols. Lucknow, (Vol. 1, Trans. H. Blochmann, Ed. & Revised D. C. Phillott). Calcutta, 1939, (Vol. 2 & 3 Trans. H. S. Jarrett, Revised J. N. Sarlcar). Calcutta, 1948.

Ashirabadi, L. S. (1962). Akbar the great. Agra.

Aslam, M. (1969). Din Ilahi our Uska Pasmanzar. Delhi.

Badauni, Abdu’l Qadir. (1864-69). Muntakhabut Tawarikh, 3 Vols. Calcutta, (Vol. 2, Trans. W. H. Lowe). Calcutta, 1898. Bayur, Y. H. (1946). Hindistan Tarihi (I-III). Ankara: TTK Basımevi.

Brown, E. G. (1930). A literary history of Persia. Cambridge.

Busch, A. (2010). Hidden in plain view: Brajbhasha poets at the Mughal Court. Modern Asian Studies, 44(2), 267-309. Chandra, S. (2007). History of Medieval India. New Delhi: Orient Longman.

Dabistan i-Mazahib ascribed to Zulfiqar Ardastani. (1843). (Trans. D. Shea & A. Troyer). 3 Vols. Paris. Habib, I. (1997). Akbar and his India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Hussain, Y. (1957). Glimpse of the Medieval Indian culture. Bombay.

Lal, K. S. (1966). Studies in Indian history. Delhi: Ranjit Printers & Publishers.

Mahmud, S. (1949). Hindu Muslim cultural accord. Bombay: Vora & Co. Publishers.

Majumder, R. C. (1949). An advanced history of India. London.

Makligon, E. (1932). The Jesuits and the Great Mughal. London.

Mehta, J. L. (1984). Advanced study in the history of Medieval India. New Delhi: Sterling Publishers. Nadwi, A. H. A. (1982). Tarikh Dawat wa Azimat Majlis Tahqiqat wa Nashriat Islam. Lucknow: Nadwatul Ulama. Prasad, I. (1974). The Mughal Empire. Agra.

Rezavi, S. A. N. (2008). Religious disputations and imperial ideology: The purpose and location of Akbar’s Ibadatkhana. Studies in History, 24(2), 195-209.

Rizvi, S. A. A. (1975). Religious and intellectual history of the Muslims in Akbar’s reign with special reference to Abu’l Fazl (1556-1605). Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Roychoudhury, M. L. (1941). The Din Ilahi. Calcutta.

Siddique, A. F. M. (2001). Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (Rh.) & his reforms. Dhaka: Research & Publication Khanka-e-Mujaddidia. Sirhindi, A. S. (1877). Maktubat Imam Rabbani. Lucknow.

Smith, V. A. (1917). Akbar, the Great Moghul, 1542-1605. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Syed, J. (2011). Akbar’s multiculturalism: Lessons for diversity management in the 21st Century. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 28, 402-412.

Unto, T. (1976). Ahimsa. Non-violence in Indian tradition. London.

Notes

Cemil Kutlutürk, Asssistant Professor, Faculty of Divinity, Ankara University; The Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies (MESAAS), Columbia University.

1 Hereupon the term “Gurkani” will be used in order to refer the Baburi Dynasty which was established by Babur in India instead of the term of Mughal or Mungol. One of the most important historians in this field, Prof. Bayur, have clearly revealed this reality by construing first hand sources (Bayur, 1946).

2 As a result of close association with Hindus and translation of some Hindu sacred texts to Persian or Arabic, Muslims began to obtain some important knowledge on Hindu religion and their history. This process on one hand enabled to some informed Muslims to discuss with Hindus in a true manner, on the other caused to reveal a new section among the Muslims who were called as “muselman hindu ve mizaj”, Hindu-minded Muslims (Siddique, 2001, p. 97).

3 Non-consumption of this kind of vegetables is one of the unique character of strict Jains. According to them tiny organisms are injured when the plant is pulled up (Unto, 1979).

4 As a result of such oppressions and unjust implements the true ulama had to leave the „Ibadat Khana‟. For example Shaikh Badrud Din, the son of Shaikh Selim Chishti, left the court of Akbar. He first went to Ajmir and then to Gujrat and ultimately to Makkah (Badauni, II/212).

5 Such an attitude committed by Shaikh Mubarak and his sons was so political and important. Because during the reign of Babur, the Caliphate was transferred to the Ottoman Empire and the Sunni Muslims acknowledged Sultan Selim as Caliph of the Muslim world. In this regard to declare Akbar as Caliph against Sultan Selim of Turkey was not possible and acceptable at that time (Siddique, 2001, p. 94).

6 According to Roychoudhry (1941), this is the only book in which the virtues of the Din-i Ilahi was expressed.

7 Though it is mostly ascribed to Muhsin Fani, the recent studies have been revealed that the writer of the text is not clear. It is also argued some scholars that in fact this book seems to have been written by Zulfaqar Ardastani (Rizvi, 1975, p. 39).